After it came up on this blog a while back, I’ve wanted to return to the topic of the “Original Aramaic Lord’s Prayer.” Why? Because the thing that can be found online referred to in this way is not original, not Aramaic, not a translation, and not the Lord’s Prayer.

Let me elaborate further.

This prayer can be found online in a number of places, and stems for the most part from books like Prayers of the Cosmos: Reflections on the Original Meaning of Jesus’s Words

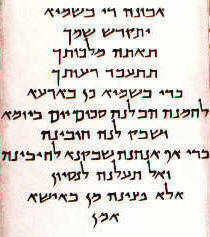

The transliteration is poor, and so anyone reading the English letters will not get a sense of what the words sound like. The transliteration is based on the Syriac version of the Lord’s Prayer. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, but it differs in some respects from Galilean and other Palestinian dialects of Aramaic, and so even to the extent that the Syriac prayer is Aramaic, it is not the original Aramaic. (Scroll to the end of the post for the text of the prayer in Syriac).

Let me go through the alleged translation of the alleged original Aramaic prayer line by line, and explain why it is not a translation of the meaning of the Aramaic into English (whether the Syriac or a reconstructed Galilean version), and thus does not deserve to be considered a form of the Lord’s Prayer.

Oh Thou, from whom the breath of life comes, who fills all realms of sound, light and vibration.

This is not a translation of either Matthew’s or Luke’s version, much less an attempt to determine which is the more original. The likelihood that Jesus’ own uttered version of the prayer, before it was adapted for communal use by Christians as reflected in Matthew, simply began with Abba, the Aramaic word for father, is likely. There is no personal pronoun, and no sense in which Abba means “one from whom the breath of life comes.” Nor does the reference to heaven/sky – again, found in Matthew but not in Luke – translate naturally to “realms of sound, light and vibration.”

May Your light be experienced in my utmost holiest.

This is clearly an attempt to do something with “Hallowed be your name.” But how does name become light, and how does the expression of a desire for the name to be sanctified become something holy in the one praying? This is not a translation or even an interpretation of what is in the Syriac, Aramaic or any other version of the Lord’s Prayer.

Your Heavenly Domain approaches.

This line is not as bad as the previous ones if considered an attempt to paraphrastically explore the meaning of Matthew’s version. But since we know that the version in Matthew, “kingdom of heaven,” is his rendering of “kingdom of God,” combining the sense that it is God’s domain with the idea that it is heavenly is potentially confusing. As for the verb, the future tense has been rendered in previous lines as expressing the desire for something to happen, and so for consistency it should be rendered the same way here: “May the domain of God come.” Otherwise, it should be “The domain of God will come.”

Let Your will come true – in the universe (all that vibrates) just as on earth (that is material and dense).

The first part of this is not bad – a very literal rendering might be “Let your will be” which can carry the sense of “Let your will happen/come to pass.” Turning the heavens into a universe that vibrates and adding commentary about density to the earth is unhelpful and does not reflect an ancient understanding, which did not necessarily view the heavens as immaterial, nor do I think that people today think of the universe as immaterial. So once again, not only is this not translation, much less good translation, but it is unnecessarily confusing.

Give us wisdom (understanding, assistance) for our daily need, detach the fetters of faults that bind us, (karma) like we let go the guilt of others.

Give us wisdom (understanding, assistance) for our daily need, detach the fetters of faults that bind us, (karma) like we let go the guilt of others.

Turning the request for bread into a request for wisdom, however much the provision of manna was treated as symbolic of the giving of wisdom, takes one well beyond translation. The second part adds karma for no reason, and this is clearly the importing of an Indian concept into what is being claimed as a first century Galilean Jewish prayer.

Let us not be lost in superficial things (materialism, common temptations), but let us be freed from that what keeps us from our true purpose.

The interpretation of temptation as having to do with superficial things and materialism, and the interpretation of evil as “what keeps us from our true purpose” is interesting and worth reflecting on, but it is not in any sense a translation of what the Aramaic words mean, but an attempt to apply the prayer to today’s very different setting. Materialism was not an issue that most of Jesus’ audience had the luxury of being tempted by.

From You comes the all-working will, the lively strength to act, the song that beautifies all and renews itself from age to age.

This has almost nothing in common with the Aramaic. The closest is its rendering of the word for power in terms of “strength to act,” since strength is indeed one of the meanings of the Aramaic word found where, in the familiar English versions, the Greek is rendered “power.” But the introduction of a song as a substitute for “glory” when the Aramaic has no musical connotations is unjustified, and so too the introduction of the notion of “will” where previously the same word for kingdom was rendered (quite legitimately, if narrowly) as “domain.”

Sealed in trust, faith and truth. (I confirm with my entire being)

I am tempted to mention that “Amen” means different things in different contexts – my pastor regularly says that in a Baptist church, “Amen” means “You may be seated.” The question of what Amen means in a lexical sense is relevant, but so too is the question of how the term functioned when used even by people who were speaking languages other than Hebrew and yet still used the Hebrew term.

In short, I have no problem with anyone who happens to want to utter this prayer or finds it meaningful or spiritually useful. Just don’t mistake it for a translation of the Lord’s Prayer, much less the original Aramaic one. The same applies to many of the other supposed translations of the Aramaic Lord’s Prayer that one can find online. In short, the less it looks like the Lord’s Prayer as you know it, the more likely it is to be a free paraphrase or interpretation rather than a translation. And if you want to really grasp the Lord’s Prayer as Jesus uttered it in his own language, there is only one way to get even close to doing that: learn the ancient Palestinian dialect of Aramaic. Translating words from one language into another always involves some transformation of meaning. There is simply no way to fully grasp the precise meaning and nuance of anything in another language than by becoming intimately acquainted with the language and culture in question.

For more on this subject, see the several relevant posts by Steve Caruso on The Aramaic Blog as well as other critical appraisals available online.