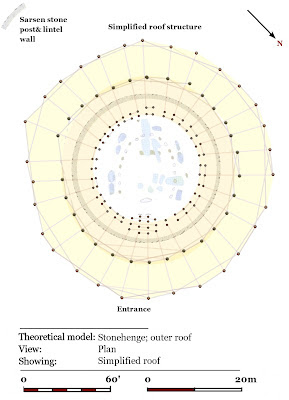

The rings of postholes at Stonehenge [Y, Z, Q, and R holes] are often ignored, or a thought to be redundant stone holes, but it is just one of a group of concentric timber structures known from various period in British Prehistory. Like Woodhenge, Durrington Walls, Mount Pleasant, and The Sanctuary, Stonhenge is a large timber building. This was tentatively recognised by Tim Darvil in 1996, who called them Class Ei structures.[1]

What I am arguing:

A: Stonehenge is a class Ei Timber structure

B: The archaeological footprint of class E structures share geometric, proportional and structural features, all of which are consistent with them being roofed buildings.

While all these structures

are unique, they are sufficiently similar in their spatial arrangements, in

ways over a dozen ways, all of which are that are best explained by the

requirements of architectural solutions directed at supporting a timber

roof. All these structures have been

discussed in earlier articles.[2]

These arguments are made

on the basis of the spatial distribution and relationships of the

archaeological plans, and are demonstrated by accurate technical diagrams.

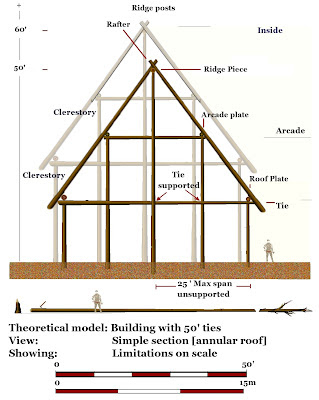

2. Form: These Class Ei structures are based on a system of 5 rows of posts; this is the form of roof evident in the Neolithic. All of the observations below are consistent with an attempt to create a roof based on this model. These round buildings are built like a series of Neolithic long houses turned in a circle. They are annular, with the tighter circles probably being covered with a central cone. Not all have 5 rings of posts, Stonehenge has 4 plus a circular wall, while Woodhenge and Durrington Walls have additional rings on the inside of the circle.

3. Later examples: These Class Ei structures are known from the late Iron Age, as at Naven fort dated to where it has a proto historical context, and is also evident in the layout of this Dark Age ringfort at Lissue.[3] This clearly argues that concentric rings of post are a technological solution to roofing circular spaces. Stonehenge is simply a particularly unique variation on a type of large building.

4. Proportion: For a roof this form to ‘work’ it must be proportional and be composed of parallel elements at different heights. Viewed in section this is broadly the case;

·

Flanked posts for an

arcade [not Stonehenge]

·

Each rafter pair is

nominally supported five horizontal parallel timbers [10 posts] with a tie at

running across the base.

·

The complexities of

this geometry are covered by reasons below [Interlace theory].

5. Posthole depth: In this form of

roof the ridge at the top is supported by posts, and this explains why the

central row of posts is usually the largest and deepest. This does not preclude a set of larger

posts on the inside of this, depending on how the roof in the centre of

the structure is fashioned.

6. Scale: Class Ei buildings are about 50’/15m across the roof; this is the traditional width for large timber buildings in Britain. Much subsequent development in architectural technology was directed towards pushing these limits, and creating space less encumbered with posts, perhaps reaching one climax with Westminster Hall, [68’(20.72m)].

7. Oak timber building: The growth pattern of

young Oak trees dictates the availability of suitable timber to form

continuous timber components like rafters and ties, when the tree is

neither too thick at one end, nor too thin at the other. For practical

purposes we can think of a 50’ /15m tree trunk tapering, this being the best

timber commonly available. [2]

- Some individual Timbers may be considerably longer up to, and even over 60’, these can be split from the trunks of larger more mature trees just as in medieval buildings.

- Prehistoric builders may have an advantage in terms of natural forest resources

- This limit is also reflected in the size of roundhouses.[2]

- Trees of this size/age range are represented in the diameter of postholes.

9. Structural detail: Spans: So it can be supported, the path of these horizontal ties across the base of the roof, directly between the corresponding inner and outer posts, will past next to, but not through, the intervening posts. The maximum unsupported timber does not exceed c.25’. At Stonehenge the ties would be supported by the center posts of the Z holes, and then from the Sarsen ring.

10. The Sarsen Ring: This is a perfectly

serviceable load baring wall.

·

Levelled

·

Engineered to a high

standard

·

Concentric with rest

of timber structure

·

Positioned like an

arcade

·

Implies the presence

of a load [roof]

11. The Trilithons: These are a load baring

post and lintel component;

·

Levelled

·

Positioned at the

centre of gravity of a conical roof based on the inner post ring [R].

12. Woodhenge: This is not a circular building, but it is the exception that proves the rule; it is based on a Lozenge, a difficult and singular shape to roof, yet it still works as a building. This geometry is shared with the Bush Barrow Lozenge, other motifs of this period

Once it is understood that these structures are

buildings, further consideration of their scale and circular geometry makes it

apparent that they cannot be simplistic in design. Accurate three-dimensional

modelling and testing has to consider more complex issues, and Interlace Theory was developed to model and understand structures with curving roofs supported by post rings.

13. Structural geometry: Interlace properties; by joining the posts of a ring to each other at different intervals, the parallel elements at different heights and angles necessary to facilitate a curving multilevel roof are created. Longer elements are higher on the widening outside surface of the roof, but lower on the inner surface. It also increases the rigidity and strength of the structure by;

·

Creating a series of

interlocking polygons

·

Interlock with the

next post ring

14.Assembly: At its most basic each section of roof, can be thought of it as five parallel pieces of wood, supporting a rafter pair, each element supported by posts in the post rings. They could be assembled by starting from the lowest section of roof; from a pair of posts in the outer ring and a set of parallel elements in the inner ring. The adjacent sections sharing one of the original posts would have to be slightly higher, and so on until a high side is reached.

· As you have to start with a tie, so the intervening posts that support it would have to be in place.

· The inner ring [s] and roof is a scaled down version [reflection] of the outer roof shape.

· The inner ring [s] and roof is a scaled down version [reflection] of the outer roof shape.

·

It is possible to

build such a structure in two directions starting at a low point.

·

It ensures that each

part of the roof is at its own unique height preventing special conflicts in a

roof that turns in on itself.

·

This implies that

these structures had a higher side, and therefore the high part of one post

ring probably roughly corresponded to the lower posts of the next ring, and so

on, allowing for a continuous build in the horizontal timbers.

· Think about bricklaying or basketry, this is a system of assembly for tree trunks; joining the post together continuously, like '70's string art, using timber instead of string, and posts rather than nails.

Conclusions

Stonehenge is unique, but

so are all the other structures discussed, however, despite this, they have a

series of features in common which could not be coincidental, and that are

entirely consistent with the proposition that class Ei buildings were roofed. There are still more reasons I could give, but it would become abstracted and technical, the Advanced Considerations are already well into architectural model making.

There is no archaeological

evidence that these structures were not buildings, only a prejudice in existing

narrative. However, a lack of structural understanding and appropriate research

to resolve the issue, cannot serve as argument that these particular

assemblages of postholes are the product of a unique, unprecedented, and

undocumented religious ritual created to explain ‘Timber Circles’. Nor is

circularity sufficient ground to infer a simplistic relationship with the Stone Circles of

earlier periods.

Clearly, this challenges

the current academic narrative, with its emphasis on the perceptions, belief,

rituals, and cosmologies of ancient peoples, none of which is implicit in the evidence

that is recovered by archaeology.

Reverse engineering

structures works by deduction, building models that work, discarding the ones

that don’t. This research did not set

out to prove anything, and certainly did not set out to understand Stonehenge

and other Ei buildings, that has been a by-product of testing ideas about postholes, that started as an enquiry into Iron Age and Roman

timber buildings back in 1990.

The scale of these structures clearly infers they were built at the limit of what was considered prudent by builders in Prehistory. This is a craft was several thousand years old, and by this period we have evidence of a new elite who would normally be expected to express wealth and power in the built environment.

The scale of these structures clearly infers they were built at the limit of what was considered prudent by builders in Prehistory. This is a craft was several thousand years old, and by this period we have evidence of a new elite who would normally be expected to express wealth and power in the built environment.

My presumption is that Stonehenge was a temple built house the Bluestones; the unprecedented use of a stone load baring wall and pillars in the centre is a technological approach reminiscent of Mediterranean Europe, suggesting imported craftsmen. But this is only the very pointy end of a much larger wedge.

The real interest lies in the many other buildings that can be understood in detail, and the new light this can shed into the nature of the prehistoric built environment.

The real interest lies in the many other buildings that can be understood in detail, and the new light this can shed into the nature of the prehistoric built environment.

The detailed understanding of how these structures worked and were assembled, briefly discussed above, allows the building of a virtual timber by timber reconstruction using CAD technology, and I will be discussing this in my paper at the CAA 2012 Conference at Southampton.

Sources and further reading

[1] ’Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond’’ (1996) Neolithic Houses in North-West Europe and beyond (Oxbow monograph 57) [Paperback]. T.C. Darvill (Editor), Julian Thomas (Editor) [Fig 6.9]

[2] Previous Articles on this site:

Bronze Age Architecture; Woodhenge

Interlace Theory; Understanding Woodhange

Debunking the myth of Timber circles

Stonehenge and the Archaeology of the Prehistoric Roof

[3] Lissue Ringfort; http://www.lisburn.com/books/historical_society/volume6/volume6-4.html

Sources and further reading

[1] ’Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond’’ (1996) Neolithic Houses in North-West Europe and beyond (Oxbow monograph 57) [Paperback]. T.C. Darvill (Editor), Julian Thomas (Editor) [Fig 6.9]

[2] Previous Articles on this site:

Bronze Age Architecture; Woodhenge

Interlace Theory; Understanding Woodhange

Debunking the myth of Timber circles

Stonehenge and the Archaeology of the Prehistoric Roof

[3] Lissue Ringfort; http://www.lisburn.com/books/historical_society/volume6/volume6-4.html

[Last Accessed 29/09/11]