One of the most interesting observations about the genetic structure of the Old World, is the fact that distantly located populations are often more similar to each other than to their more immediate geographic neighbors.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

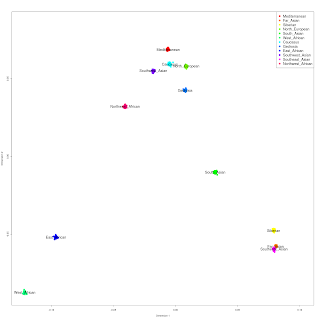

For example, in my recent K12a admixture experiment, the six components. I named Mediterranean, North_European, Caucasus, Gedrosia, Southwest_Asian, and Northwest_African have a maximum Fst between any two of them of 0.073 (between Gedrosia and Northwest_African), and a mimimum Fst between any of them and any of the others of 0.075 (between Gedrosia and South_Asian). Henceforth, I will call these six components simply "the Six."

It is remarkable that "Gedrosia", the component peaking in present-day Balochistan is about equidistant to the component peaking in Mozabite Berbers ("Northwest_African") and that peaking in South Indian Dravidian speakers ("South_Asian"). Going by geography alone, and even if we calculated distances "as the crow flies" and ignored all natural obstacles between Balochistan and the Sahara, we would have expected "Gedrosia" to be about 3 times more distant to "Northwest_African" than to "South_Asian".

Divergence between populations across the entire genome builds up mainly by two processes:

- Genetic drift

- Admixture

Moreover, if these populations migrate from their original homeland and absorb the indigenous inhabitants wherever they go, then they will diverge even more, depending on how much admixture they undergo, and how distantly related the aboriginal inhabitants are.

Clik here to view.

It is clear that admixture has played a role in the overall divergence of the Six. For example, the Northwest_African component is shifted (relative to the remaining five) towards the other African components; the Southwest_Asian is also thus shifted, but less noticeably. The Gedrosia component is shifted towards the South_Asian one; and the easternmost components, the North_European, and Gedrosia ones, are shifted towards the Asian components.

All these shifts are quite salient in the MDS plot, and there is ample evidence for the aboriginal populations being shifted in the expected direction in each region.

We can calculate the median Fst within the Six: it is 0.053, as well as the median Fst between members of the Six and all the rest: it is 0.13. The ratio of the two is ~40%. Of course, the various components have diverged from each other at different times: West and East Eurasians, for example, began diverging shortly after both diverged from Africans. Nonetheless, we can (conservatively) place the divergence time of the ancestors of the Six from East Asians, Ancestral South Indians, and Sub-Saharan Africans, at around 40,000 years ago, the time when the Upper Paleolithic (and modern man) makes its appearance all over the Old World.

Actual divergence times may be lower, and this is why 40k is a conservative estimate. The point of this back-of-a-napkin calculation is to give a rough estimate, rather than a precise date.

Assuming that Fst builds up roughly linearly with time due to drift (again a simplification), we can estimate that divergence within the Six dates to less than 16 thousand years ago. This may be an overestimate for two reasons:

- Divergence between Proto-West Eurasians and the rest of mankind may be less than 40k years

- Each of the Six have partially absorbed aboriginal inhabitants (e.g., Palaeo-Europeans, Ancestral South Indians, Pre-Berber North Africans, etc.) that spent most of the Paleolithic diverging from the common ancestors of the Six.

The womb of nations

Clik here to view.

The Neolithic of West Eurasia started, by most accounts, c. 12 thousand years ago. Its origin was in the area framed by the Armenian Plateau in the north, the Anatolian Plateau in the west, the Zagros Range in the east, and the lowlands of southern Mesopotamia and the Levant in the south. Intriguingly, the prehistoric site of Göbekli Tepe sits right at the center of this important area, in eastern Anatolia/northern Mesopotamia.

If there is a candidate for where the ur-population that became the modern Six lived, the early Neolithic of the Near East is surely it. This hypothesis makes the most sense chronologically, archaeologically, genetically, and geographically.

Migrants out of the core area would have spread their genes in all directions, becoming differentiated by a combination of drift, admixture, and the selection pressures they faced in different natural and cultural environments; some of them would acquire lighter pigmentation, others lactase persistence, malaria resistence, the ability to process the dry desert air or to survive the long winter nights of the arctic. These spreads were sometimes gradual, sometimes dramatic: they took place over thousands of years and from a multitude of secondary and tertiary staging points.

In Arabia, the migrants would have met aboriginal Arabians, similar to their next door-neighbors in East Africa, undergoing a subtle African shift (Southwest_Asians). In North Africa, they would have encountered denser populations during the favorable conditions of MIS 1, and by absorbing them they would became the Berbers (Northwest_Africans). Their migrations to the southeast brought them into the realm of Indian-leaning people, in the rich agricultural fields of the Mehrgarh and the now deserted oases of Bactria and Margiana. Across the Mediterranean and along the Atlantic facade of Europe, they would have encountered the Mesolithic populations of Europe, and through their blending became the early Neolithic inhabitants of the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe (Mediterraneans). And, to the north, from either the Balkans, the Caucasus, or the trans-Caspian region, they would have met the last remaining Proto-Europeoid hunters of the continental zone, becoming the Northern Europeoids who once stretched all the way to the interior of Asia.

Clik here to view.

It is, perhaps, in the ancient land of the Colchi, protected by the Black and Caspian seas, and by tall mountains on the remaining sides, that something resembling the ur-population survived. The great linguistic diversity of the Caucasian peoples, the central position of the Caucasus component among the Six (see MDS plot), and the fact that theirs was a remote region, ignored by the empires of the Near East to the south, and the frequent travellers of the Eurasiatic steppe to the north, may all indicate the plausibility of this assertion. Through a peculiar coincidence, old Blumenbach may have been onto something, although for reasons he could scarcely have imagined.

We don't have to suppose that a single process drove the dispersal of genes from the core area of the Near East. Agriculture was definitely an early facilitator of dispersal, but a variety of technological developments may have been instrumental in further spurts of dispersal: the invention of pottery, metalworking, pastoralism, sea navigation, the engines of war, all the way to the recent past, when ocean-going vessels from Western Europe sailed to the New World, Arab merchants and warriors spread their new religion to the continent of Africa, and Russian hunters and farmers began the conquest of Siberia.

There are hints that scientists are beginning to realize that this story may describe what happened during prehistory. The next few years will help resolve this grand puzzle of "how West Eurasians came to be."

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.