Colloque international organisé par :

Hedwige Rouillard-Bonraisin (EPHE - UMR 8167)

Maria Grazia Masetti-Rouault (EPHE - UMR 8167)

Jean-Michel Verdier (EPHE)

Christophe Lemardelé (EPHE - UMR 8167)

Corps, âmes et normes : approches cliniques, légales et religieuses du handicap

Late Roman Economy and Formation Processes

I’ve spent some quality time with the most recent volume of Late Antique Archaeology this past month in preparation for writing a short contribution with David Pettegrew on connectivity in the Late Roman eastern Mediterranean. We plan to compare the Late Roman assemblages produced by two survey projects: Eastern Korinthia Archaeological Project and Pyla-Koutsopetria Archaeology Project. An important component of both assemblages is Late Roman amphoras: EKAS produced substantial quantities of Late Roman 2 Amphora probably produced in the Argolid; PKAP produced quantities of Late Roman 1 Amphora produced both on Cyprus and in southern Cilicia. We hope to discuss how the concentrations of these common transport vessels reflected and complicated how we understand economic patterns in the Late Antiquity.

Over the past half-century two basic models for the Late Roman economy have emerged. The earlier models saw the state as the primary engine for trade in antiquity. More recently, however, scholars have argued that the core feature of ancient trade is small-scale interaction between microregions across the Mediterranean basin. While there is undoubtedly some truth in both models, the latter has substantially more favor among scholars at present and the volume dedicated to connectivity focuses on the kind of small-scale interregional exchange that created a network of social, economic, and even cultural connections that defined the ancient Mediterranean world. The classic question introduced to complicate our view of ancient connectivity is: if the ancient Mediterranean is defined by these small-scale connections, then why did the political, economic, social, and even cultural unity of the communities tied to the Middle Sea collapse with the fall of Roman political organization in Late Antiquity?

This is where David and I want to introduce the complicating matter of formation process archaeology. The substantial assemblages of Late Roman amphora represent the accumulation of discard from two “nodes” within the Late Antique economic network. These two nodes, however, are particularly visible because of the substantial concentration of a class of transport vessel.

These transport vessels most likely served to transport supplies to imperial troops either stationed in the Balkans or around the Black Sea, or in the case of the Eastern Korinthia, working to refortify the massive Hexamilion Wall that ran the width of the Isthmus of Corinth or stationed in its eastern fortress near the sanctuary of Isthmia. The visibility of these two areas depends upon a kind of artifact associated with a kind of exchange. As David has noted the surface treatments associated with LR2 amphora make them highly diagnostic in the surface record. LR1s, in turn, have highly diagnostic, twisted, handles that make them stand out from a surface assemblage dominated by relatively undifferentiated body sherds. In other words, these amphora assemblages represent a visible kind of economic activity.

The impact of this visible type of economic activity on our understanding of Late Roman connectivity is complex. On the one hand, the kind of persistent, low-level, economic connections associated with most models of connectivity are unlikely to leave much evidence on the surface. The diverse and relatively small group of very diverse amphoras, for example, found upon the coasting vessel at Fig Tree Bay on Cyprus would have been deposited at numerous small harbors along its route. Moreover, the fluidity of the networks that characterized connectivity would have made the routes of caboteurs irregular and contingent on various economic situations throughout the network of relationships. This variability and the small-scale of this activity is unlikely to have created an archaeologically visible assemblage at any one point on these routes. More than this, overland trade in wine or olive oil may not have used amphoras at all further impairing the archaeological visibility of the kind of low-level connectivity characteristic of Mediterranean exchange patterns. Between ephemeral containers and variable, low-density scatters, the regular pattern of archaeological exchange characterizing connectivity will never be especially visible in the landscape.

In contrast, imperial provisioning requirements, fueled for example by the quaestura exercitus, would present exceptionally visible assemblages of material. The interesting thing, to me, is that the amphoras visible on the surface in the Korinthia and at Koutsopetria are not what is being exchanged, but the containers in which exchange occurs. The material exchanged, olive oil and wine, are almost entirely invisible in the archaeological records on their own. The visibility of these two places reflects the presence of outlets for a region’s produce. The produce itself, however, leaves very little trace, and we have to assume that networks that integrated microregions across the Mediterranean functioned to bring goods from across a wide area to a particular site for large-scale export.

The collapse of these sites of large-scale export during the tumultuous 7th and 8th centuries did not make trade between microregions end, but it made it more contingent and less visible, as I have argued for this period on Cyprus. The absence of large accumulations of highly diagnostic artifact types in one place represent a return to our ability to recognize normal patterns of Mediterranean exchange as much as the disruption of this exchange. The decline of these sites both deprived archaeologists of visible monuments of exchange and ancient communities of a brief moment of economic stability within longstanding contingent networks.

My Time with the Associates for Biblical Research at Khirbet el Maqatir in Israel

Canterbury dig uncovers Britain's oldest road

Hundreds of people in Canterbury took to the city’s Westgate Parks, to take part in an archaeological dig that uncovered Roman artefacts, treasures, and Britain’s oldest road.

Over six hundred people stopped by the community dig over the three-day weekend, to see some of the amazing finds unearthed by more than seventy members of the community, volunteers from the Friends of Westgate Parks, and members of the Canterbury Archaeological Trust.

The dig unearthed a part of the Roman Watling Street, the ancient trackway between Canterbury and St Albans. Read more.

Le Fluff et Le Puff ... Or How I Love The Gap

But since I tend to wear the same gear at sites as I do walking Ellie ...

These PJs are from The Gap (here) and I wish I'd picked them up as after the flood I'm away and ... the red flower coulourway doesn't photograph well but is feminine without being girlie.

I highly recommend signing up for The Gap's mailing list as they often sent discount vouchers ....

The trousers I've been living in are the Broken-in straight linen pants from The Gap (here) in blue, and white ... and I miss last summer's green ones that are RIP.

(I can't find the perforate suede ballet pumps on the web site, but some stores still have them in the sale section).

The grey cotton jumper I've been living in is from ASOS (£15 here in the sale) - it's a bit oversize so I'd go down a size, and washes fine in the machine.

As the temperatures are dropping, I'll be moving into my trusty black Slim Cropped pants from The Gap (here). Ignore the awful styling on the web site, they are fabulous with flats or even heels.

I also picked up this olive Military Jacket from The Gap (here) - I wish they'd made them all an inch or two longer but it's great for dog walking, and has pockets for poop bags and treats and ...

I wish, I wish, I wish I'd managed to get this dress, but it's almost sold out in the UK, not on The Gap's web site any more, and only in the most miniscule of sizes in shops ... In the US of course it's on sale and available in every size (here). Grrr.

The Gap in the US also has these (here), which I'd have snapped up in a heartbeat and provided a loving home to ...

Instead I got these Juju Black Chelsea Jelly Ankle Boots which are far more practical - and far chicer than the overly ubiquitous Hunters. They're at Asos here; I wish I'd grabbed their biker boot wellies too ...

I also got this cotton striped jumper from ASOS (£14 in the sale here).

And hopefully The Gap will have more of their fabulous cosy cashmeres in soon ...

About two-thirds of my tees are from The Gap - about half are the classic plain and simple Pure Body ones (here), the rest from various of their collections over the years.

Superintendent Osanna to speak in Munich

Der Vortrag wird am Montag, den 15. September, am Lehrstuhl für Restaurierung, Kunsttechnologie und Konservierungswissenschaft der TU München stattfinden.

Alle notwendigen Informationen bezüglich des Vortrages finden Sie in der Einladung, die ich Ihnen im Anhang dieser Email sende.

Für Rückfragen stehe ich Ihnen natürlich jederzeit gerne zur Verfügung,

Anna Anguissola

------------

Dr. Anna Anguissola

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Graduate School Distant Worlds

Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1

D-80539 München

Maps for Teaching Paul

The site “Vox” shared a set of “40 Maps that Explain the Roman Empire.” A number of them are interesting for those who teach Biblical studies. Since I am teaching a class on Paul and the early church this semester, a couple seemed particularly relevant. For instance, this one seems like it might help students in the United States grasp the geographic extent of the Roman Empire:

And this one, showing distances in terms of travel time, is likewise of particular relevance in conveying what was involved in Paul’s travels:

I am less happy with this one, which seems to give an impression of complete Christianization by region, whereas it would be more accurate to say that this depicts regions where Christianity could be found in the periods indicated:

Among the assignments that students can submit in the class this semester, making maps of their own is an option. What maps do we not have readily available online, which would help explain something about Paul’s life and activity? My students might benefit from your suggestions.

The Corinth Excavations

Fig. 1. The Temple of Apollo at Corinth. This is the view I see each day as I walk from the excavation house to the Museum.

I am writing from the site of Ancient Corinth, where excavations under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens have been going on since the late 19th century. The Corinth Excavations have been a training ground for generations of archaeologists, including me, and I thank the director, Guy Sanders, and assistant director, Ioulia Tzonou-Herbst, for making Corinth such a wonderful place to work. I’ve been working at Corinth for a long time, so I’m also indebted to the director emeritus, Charles Williams, and the assistant director emerita, Nancy Bookidis, for a scholarly lifetime of support, encouragement, and friendship.

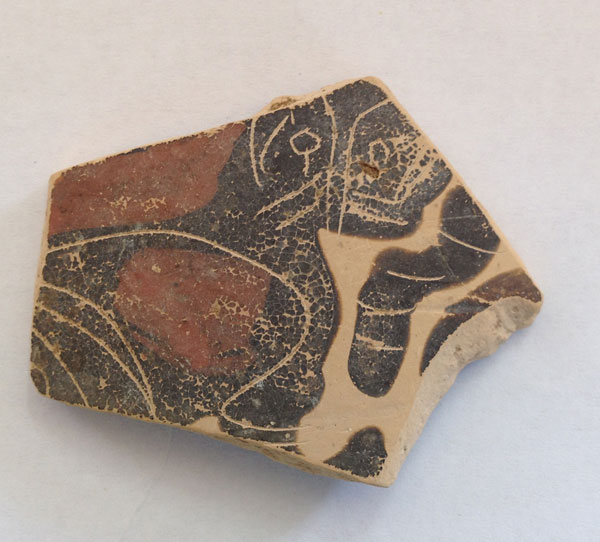

At Corinth, I am working on late seventh and early sixth century BCE pottery from the area known as the Potters’ Quarter. Up next to the city wall on the west side of the city, the Potters’ Quarter is one of the sites around the city where pottery was produced. The Potters’ Quarter was excavated by Agnes Newhall Stillwell, a graduate of Bryn Mawr College, for several years beginning in 1929, when she was a fellow at the American School. No kilns where the pottery was fired have been discovered in the Potters’ Quarter, but the large quantities of damaged–misfired, cracked, misshapen–pottery as well as much material associated with pottery production, especially try-pieces, that are found in fills and deposits make clear that pottery was produced nearby.

I am working on the very large quantity of material from a well–Well 1929-1 in Corinth nomenclature–in the Potters’ Quarter. The well was dug in the 7th century BCE and once it went dry, it was filled up with quantities of pottery, discarded no doubt from nearby potteries. Some of the pottery from the well was published by Stillwell and J. L. Benson (Corinth XV:3: The Potters’ Quarter: The Pottery. Princeton 1984), but much remained unstudied and that is what I am working on. I am particularly interested in the different painters whose work is represented in the well’s contents, and here I’ll focus on the painters of the shape known in Corinth as the kotyle. It’s the same as a skyphos, a deep two-handled drinking cup, and the kotyle is very common in Corinthian pottery of the late seventh to mid-sixth centuries BCE. Some Corinthian kotylai (the plural of kotyle) are very fine, but not the ones I’m working with. An example, Corinth C-31-46, (fig. 2) from elsewhere at Corinth shows the shape–only one handle is visible here–and the decorative scheme, which includes a figural zone that here has an elongated panther and part of another animal.

Fig. 3. Philadelphia 49-33-26

I have grown quite familiar with the style of these Corinthian kotyle painters, and one day, a few years ago, when I was looking a drawer of pottery sherds in the Mediterranean Section, I saw a small fragment by a painter well known to me from the kotylai of my Potters’ Quarter well. The fragment, 49-33-26 (fig. 3), is part of a small study collection of Greek pottery, some of it from the Potters’ Quarter, which came to the Museum sixty-five years ago thanks to the generosity of the Greek government. The Penn fragment is the work of an artist we call the Painter of KP- 248, whose name vase is from the Potters’ Quarter. That fragment preserves the head of a panther, and you can see that same panther face in another little sherd, Corinth L-29-10-302, (fig. 4) also by the painter and also from the well. And you see it again in the group of joining fragments, Corinth L-29-10-92, (fig. 6) which preserves about a third of the kotyle and has two elongated panthers (the head of the panther at the right is not preserved); these fragments are from the well and are the work of the Painter of KP-248. The Painter of KP-248 was clearly painting his kotylai at a pretty rapid rate and usually stretches out his animals so that there’s only room for three in the picture zone.

To see how the style of the Painter of KP-248 is different from that of other Corinthian vase-painters, compare it to that of the kotyle Corinth C-31-36 above (fig. 2), again from elsewhere at Corinth, and also to this other kotyle fragment, L-29-10-11, (fig. 5) from the well, by an artist also named for a complete kotyle in the well, the Painter of KP-14 (Yes, the painters have boring nicknames. Of course, we don’t know the painters’ real names, so we give them nicknames, sometimes rather dull ones.). You can see that the painters use the same idiom as they delineate their panther faces, with eyes flanking a prominent nose ridge, curved ears a little like leaves, and little lines to mark the muzzle or the whiskers. But you can also see how alike the Painter of KP-248′s kotylai are and how different they are from the others, how different the details of the style of the Painter of KP-248 are from those of the other painters.

The group of joining fragments, Corinth L-29-10-92 (fig. 6) by the Painter of KP 248, shows some variation in color because of problems with the firing. You can see the animals and ornament are brownish instead of black, and there’s a reddish area on the top of the left panther’s head, on the right panther’s tail, and on the dots of fill ornament above the right panther’s back. This reminds us of the extensive and important evidence that the material from the Potters’ Quarter provides for the study of the technology of pottery production. And a new generation of scholars is discovering the significance of the Potters’ Quarter material, through new technical and scientific studies. Amanda Reiterman (fig. 7), graduate student in Penn’s Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World program and Kolb Junior Fellow, and Bice Peruzzi, a graduate student at the University of Cincinnati, are doing new technical and scientific studies of the Potters’ Quarter material so that we may better understand pottery production and technology in the Corinth of the seventh and sixth centuries BCE.

A Glance into the Lives of the Roman Peasantry: Four Weeks of Excavation with the Roman Peasant Project

This summer, I had the pleasure of being accepted to be a part of the sixth and final season of the Roman Peasant Project. I excavated alongside a team of professional archaeologists, professors, and graduate, PhD, and undergraduate students in rural Tuscany in Cinigiano, a municipality in the Province of Grosseto. The site we excavated was called Tombarelle. The Roman Peasant Project, directed by Kim Bowes, Cam Grey, Emanuele Vaccaro, and Mari Ghisleni, is one of very few archaeological excavations that seeks to uncover and investigate the lifestyles of peasants in the Roman period. Since a great majority of the material culture of Roman antiquity represents persons of wealth and status, this project is very important for expanding the views gathered from these traditional sources. Being the final season of the project, I was very excited to learn of the accumulation of data over the years and the conclusions drawn from the evidence discovered across rural Tuscany.

Having had no previous experience in archaeology, with the exception of an introductory course taken during the first semester of my freshman year, I quickly learned the elementary concepts of rescue-style excavation. Unlike tradition excavation, this style of archaeology requires the digging and investigation of an area to occur at a brisk pace. The four trenches we excavated were first discovered through use of an archaeological survey. They were dug quickly and were some of the many areas of interest for excavation in Cinigiano. Following the survey, an excavator was called to remove the first few layers of soil, and we began the excavation by troweling in order to clean the trenches. It was quite a funny thing for one to “clean” dirt, and I have to say, I enjoyed every minute of it.

Discovering artifacts and new methods of surveying was both a very entertaining and exciting endeavor. Within the first week, we began work with pick axes and shovels and discovered our first finds of the excavation, with many of them dating from the fifth century AD. When a found had been made, a series of happy squeals emanated from those of us new to the field of archaeology. By the end of the second week, I had not only worked on every area of the dig site, but also had also learned to take measurements with a dumpy level. This required me to look through a leveled instrument to read certain heights on a measurement stick, almost like peering through a telescope at a vertical ruler. After taking the level of a small find and a fixed point, a small amount of math was applied to find the height of the artifact in respect to the sea level. Whenever such a prominent small find was uncovered, like a piece of Roman glass, for example, a dumpy level and a total station would be the instruments used to document the location of said small find.

I worked primarily in two trenches during the duration of the excavation. For the first week and a half, I worked mainly on a structure thought to be a cistern. By the end of the dig, we discovered that it had, indeed, been used as a cistern during Roman times but had been reconditioned to serve as a basement of a medieval tower. It was in trench 17000, however, where I spent most of the hours and the remaining two and a half weeks of the excavation. During the third week of excavating trench 17000, we uncovered a tile floor, mostly flat. This floor was surrounded on two sides by what appeared to be walls. This building could very well have been a Roman house. In addition to learning the physical aspects of an archaeological excavation, I learned how to fill out context sheets for my trench and transcribe the written context sheets onto a computer database.

Our finds led us to question the complexity of what a Roman peasant truly was. The peasants we studied in Cinigiano lived in rural societies. It is unknown, however, if they were as poverty-stricken as traditional views would relay. It was interesting to discover that the evidence from the material culture we unearthed suggested that the Roman peasants of this area had a great knowledge of the world outside of their farms and agricultural societies. Throughout the course of the dig, we unearthed pottery sherds, including some pieces of Terra sigillata, animal bone fragments, and pieces of tile and imbrex. Many of the pottery sherds we found were from pots and amphora that were replicas of original pieces found elsewhere across the Roman Empire. Two particular potsherds that we found had leaf-like designs etched into the clay. The pottery specialists on the excavation confirmed that these particular pieces were, indeed, reproductions of the originals. In respect to the animal bones we found, which were the bones of both cows and pigs, some possessed gnaw marks while others did not. This could suggest that these animals, in addition to being raised for sustenance, were used for certain manufacturing purposes. The building we found, if not a house, could have been a tannery or a farm. It could have also served another industrial purpose. This suggests that these peasants were involved in the manufacturing of, importation, and exportation of goods for trade.

My experience with the Roman Peasant Project in Cinigiano was an amazing one. Not only did I learn about the field of archaeology as a whole, but also I met many outstanding friends and scholars. We spent many days laughing and singing in the trenches and many late nights talking after dinner about careers, the future, favorite television shows, and, of course, the ancient world that we were attempting to uncover. My first bout with archaeology may not have been quite so exhilarating as Indiana Jones might have found it, but, in all honesty, I probably had just as much fun as the good doctor.

Now Available in Canada: Satellite Bible Atlas

The Satellite Bible Atlas now has a Canadian distributor. Until now, shipping to Canada from the U.S. cost nearly as much as the book itself. The Family Christian Bookstore in Ontario now sells the atlas, and shipping charges are much more reasonable to Canadian addresses. The Bible Lands Satellite Map is also available.

Archaeology Day at Spiro Mounds

International Archaeology Day

Thursday, October 16, 2014 - 2:00pm

Ancient tombs damaged in construction in Istanbul’s historical peninsula

Two ancient tomb covers, which were found during the rehabilitation of an underpass in Istanbul’s historical peninsula, have been delivered to Istanbul Archaeology Museum, but only after being damaged in the construction work.

The tomb parts were discovered while a bulldozer was working to remove asphalt on the Vezneciler Underpass, next to the main door of Istanbul University, as part of a project which started Aug. 5. The Istanbul Archaeology Museum was informed when the tombs were found, albeit after they were damaged due by the heavy construction vehicle.

The area was defined as a “necropolis” in the ancient era of the city. Read more.

Partially Open Access Journal: Eikasmos: Quaderni Bolognesi di Filologia Classica

Eikasmos: Quaderni Bolognesi di Filologia Classica

Fondata da Enzo Degani nel 1990, la rivista «Eikasmós. Quaderni Bolognesi di Filologia Classica» si è sempre caratterizzata per una vocazione squisitamente critico-testuale ed esegetica (la prima sezione di ogni numero è per l'appunto di «Esegesi e critica testuale»), per una rigorosa attenzione alla storia della filologia classica (cui è consacrata la seconda sezione di ogni volume) e per un costante impegno di aggiornamento e valutazione degli studi del settore (alle recensioni e alle segnalazioni bibliografiche sono riservate le ultime due sezioni della rivista).

Founded by Enzo Degani in 1990, the review «Eikasmós. Quaderni Bolognesi di Filologia Classica» is devoted to textual criticism and exegesis (the first section of each issue is dedicated to «Esegesi e critica testuale»), to the history of classical scholarship (the second section of each volume), and to a systematic and up-to-date survey of scholarly works in the fields of classical studies (the two last sections of each issue include reviews and a bibliographical supplement).

Collection «Eikasmós Online»1. Claudio De Stefani, Galeni De differentiis febrium versio Arabica (Bologna 2004)

2. Barbara Zipser (ed.), Medical Books in the Byzantine World (Bologna 2013)

Open Access Journal: Forum Archaeologiae - Zeitschrift für klassische Archäologie (FARCH)

Das Forum Archaeologiae versteht sich als Plattform, die Archäologen sowie Vertretern verwandter Wissenschaftszweige ein Medium zur Publikation ihrer Arbeiten im Internet bieten will. Das Forum entstand im Jahre 1996 aus der privaten Initiative der Herausgeber und ist finanziell sowie institutionell unabhängig. Das Forum Archaeologiae will sowohl Autoren als auch Interessierten einen unbürokratischen, kostenlosen und direkten Zugang zu aktuellen Publikationen und den medialen Möglichkeiten des Internet bieten.

Seit der 20. Ausgabe hat das Forum Archaeologiae nunmehr eine - wie wir hoffen - endgültige Heimat im Internet gefunden. Es erhielt im September 2001 seine eigene Domain unter http://farch.net (oder http://www.farch.net).

AKTUELLE AUSGABE

Mithras & Co

G. Kremer

Colophon 2013

U. Muss u.a.

Toçak Dağı (Lykien)

M. Seyer, H. Lotz, P. Brandstätter

Pelagios

R. Simon15. Archäologentag

AUSGABE 70/III/2014

Programm

G. Grabherr, E. Kistler

Mykenisches

K. Bernhardt

Prozession

F. Blakolmer

Cauponae

A. Calabró

Merkurstatuetten

A. Drack

Carnuntum

M. Grossmann

Christl. Lampen

St. Hofbauer

Bonda Tepe/Limyra

O. Hülden, S. Mayer, U. Schuh, B. Yener-Marksteiner

Zwischengoldglas

J. Köck

Brigantium

J. Kopf

Steinbruch

G. Kremer

A. Conze

K.R. Krierer, I. Friedmann

Hypokausta

H. Lehar

Pheneos

M. Lehner, S. Tausend, K. Tausend

Side

U. Lohner-Urban

Peloponnes

H. Maier

Thalerhof

P. Marko

Vindobona

M. Mosser

Brigantium

K. Oberhofer

Castelinho dos Mouros

K. Oberhofer

Monte Iato

B. Öhlinger

Götter

T. Osada

Foce del Sele

D. Probst

Aphrodisias

U. Quatember

Hanghaus 2

E. Rathmayr

St. Pölten

R. Risy

Opferfleisch

V. Sossau

Grabstelen

E. Tanaka

Troesmis

A. Waldner

Bier

J. Weilhartner

Mittelhelladikum

M. Zavadil

AUSGABE 69/XII/2013

Tischgeschirr

S. Jäger-Wersonig

Hekatombe

Hannes Lehar

Fundort Wien

Stadtarchäologie Wien

Echt?

Kathrin B. Zimmer

AUSGABE 68/IX/2013

ΦΥΤΑ ΚΑΙ ΖΩΙΑ

Programm

C. Lang-Auinger, E. Trinkl

Festvortrag

E. Böhr

Flowers

I. Algrain

Swans

Ch. Avronidaki

Figurenvasen

St. Böhm

Euboean

M. Chidiroglou

Ivy

F. Díez Platas

Exotische Tiere

G.R. Dumke

Kommunikation

B. Franke

Plastic Vases

J.R. Guy

Animal-Skins

A. Harden

Marine Life

K. E. Heuer

Tanzpartner

E. Hofstetter

Horses

M. Iozzo

Floral Motif

N. Kéi

Women & Animals

S. Klinger

Grenzfälle

J. Lang

Bees

N. Levin

'Randfiguren'

A. Lezzi-Hafter

Eros

E. Manakidou

Birds

A. Mackay

Thyrsos

V. Meirano

Pferde

H. Mommsen

Sea Voyages

J. Neils

Schlange & Eule

N. Panteleon

Dogs

A. Petrakova

Efeu & Rebe

L. Puritani

Rochen

M. Recke

Tierfries

B. Reichardt

Snakes

D. Rodríguez Pérez

Natur & Kultur

A. Schnapp

Akanthus

N. Sojc

Reittiere

M. Stark

Kyathoi

D. Tonglet

Heuschrecken

C. Weiß

'Kontraste'

L. Winkler-Horaček

Etruskisch

M. Wullschleger

AUSGABE 67/VI/2013

InterArch

M. Mele

Repolusthöhle

D. Modl

Carnuntum/Christentum

G. Kremer, A. Pülz

Brot & Wein

M.W. Pacher

AUSGABE 66/III/2013

3D Models

B. Breuckmann, St. Karl, E. Trinkl

Römische Steine

I. Egartner

Side 2012

U. Lohner-Urban

Prospektion

T. Neuhauser, O. Pink, S. Zenz

AUSGABE 65/XII/2012

Defensive Armour

M. Mödlinger

Kolophon 2012

V. Gassner, U. Muss, E. Draganits

Hausham 2012

V. Gassner, R. Ployer

Fundort Wien

Stadtarchäologie Wien

Textilarchäologie

E. Trinkl

AUSGABE 64/IX/2012

Velia 2012

V. Gassner, D. Svoboda

Soccer ball

J.W.A.M. Janssen

Römische Villen

S. Lamm

Römisches Leben

E. Rathmayr

Rhamnous

K. Spathmann14. Archäologentag

AUSGABE 63/VI/2012

Programm

P. Scherrer

Rekonstruktionen

T. Alusik, A.B. Sosnova

Atrium

M. Auer

Radmuster

C.M. Behling

Min. Götter

F. Blakolmer

Spätantike

M. Bru Calderon

Laßnitztal

G. Fuchs

Restaurierung

R. Fürhacker, A.-K. Klatz

Medizininstrumente

K. Gostenčnik

Stillfried

M. Griebl, I. Hellerschmied

Farbbestimmung

Th. Hagn

Archäobiologie

A.G. Heiss, R. Drescher-Schneider

Fibeln

D. Knauseder

Zwischengoldglas

J. Köck

Tavium

G. Koiner, Ch. Zinko

Brigantium

J. Kopf

Steine/Carnuntum

G. Kremer

Noricum/Pannonien

S. Lamm

Alexandria

A. Landskron

Ziegelöfen

F. Lang, R. Kastler, Th. Wilfing, W. Wohlmayr

Tempelzugänge

C. Lang-Auinger

Hypokaustum

H. Lehar

Pheneos 2011

M. Lehner, K. Tausend

Side 2011

U. Lohner-Urban, E. Trinkl

Epetion

T. Neuhauser, M. Ugarković

Miróbriga

K. Oberhofer

Arch. Sizilien

B. Öhlinger

Parthenon

T. Osada

Latrine/Carnuntum

B. Petznek

Chrono-Media

M. Christidis, O. Pink

Hausruckviertel

R. Ployer

Freidorf

G. Praher

Damianosgrab

U. Quatember, V. Scheibelreiter-Gail

Wohneinheit 7

E. Rathmayr

Limyra

M. Seyer

Eucarpus

St. Sitz, M. Auer

Noreia

K. Strobel

Wohlsdorf

A. Szilasi

Immurium

B. Tober

Logogramme

J. Weilhartner

Weitendorf

J. Wilding

A. Schober

G. Wlach

AUSGABE 62/III/2012

Keramikwerkstatt

H. Schörner

Amphorae/Ephesos

T. Bezeczky

Velia 2011

V. Gassner

Zafar/Jemen

L. Pecchioli, P. Yule, F. Mohamed

AUSGABE 61/XII/2011

Drachen

B. Grammer

Grotte Chauvet

U. Simon

Fundort Wien 2011

Stadtarchäologie Wien

AUSGABE 60/IX/2011

In Memoriam F. Brein

B. Kratzmüller et al.

Domplatz/St. Pölten

R. Risy

Hetäre?

M. Xagorari-Gleißner

AUSGABE 59/VI/2011

Hadrianstempel

U. Quatember

Publikation Keryx

P. Scherrer

Journalismus

E. Holzer, O. Pink

Denkmalschutzmedaille

E. PielerNÖ Landesausstellung

AUSGABE 58/III/2011

Zur Philosophie

E. Bruckmüller

Gesamtmodell

Ch. Gugl et al.

Therme

F. Humer

Götter-/Menschenbilder

F. Humer

Vermittlung

M.W. Pacher

Erobern/Entdecken

E. Bruckmüller

Objektdatenbank

M. Pregesbauer et al.

AUSGABE 57/XII/2010

Löwentor, Mykene

F. Blakolmer

Sepulkralstrafen

K. Harter-Uibopuu, V. Scheibelreiter

Kleininschriften

R. Wedenig

Fundort Wien 2010

Stadtarchäologie Wien

AUSGABE 56/IX/2010

Amphitheater, Carnuntum

D. Boulasikis

Siedlungen, Attika

M.B. Cosmopoulos

Krieg, Israel

R. Feldbacher

Antikenhandel

M. Müller-Karpe

Chichen Itza

A. Guida Navarro

Statue, Delphi

A. NordmeyerArchaeology in Confllict

AUSGABE 55/VI/2010

Program

Preface

F. Schipper

Setting the Agenda

F. Schipper,

M.T. Bernhardsson

"MY heritage"

L.E. Babits

Leipheim excavation

M. Bletzer

Illicit Traffic

K. Bogoeski

"Embedded" Archaeology

A. Cuneo

Provenance

S. Di Paolo

Interpol

A. Gach

Project ORCHID

P.R. Green

NGOs' Initiatives

S. Guner

NGO & Illicit Trade

S. Guner

Atatürk & Heritage

S. Guner, M. Yildizturan

Cypriot Antiquities

S. Hardy

Past - Future

V. Higgins

Legal Aspects

UNESCO

Military's Role

A. Kapornaki

Occupied Palestine

A. Keinan

Renovation/Afghanistan

H. Leijen

Student Perspective

D. McGill

Archaeology/Africa

C. Näser, C. Kleinitz

Scientific Organizations

B. Nelson

Cultural Intelligence

E. Nemeth

Missions to Babylon

A. Peruzzetto, J. Allen, G. Haney, G. Palumbo

Masada Myth

M. Pfaffl

Embedded Anthropologists

J. Price

Plane/Nynice

M. Rak, J. Vladar

Ziggurat at Aqar Quf

B.A. Roberts

Palestine/Brazil

G. Barbosa Rodrigues

Turkish Museums

O. Sade-Mete

Next Generation Project

A. Sands, K. Butler

Heritage in Peru

D.D. Saucedo Segami

Liasion Officer

H. Speckner

Looting and Plundering

H. Szemethy

United Arab Emirates

J.J. Szuchman

First Aid/ICCROM

A. Tandon, S. Lambert

Politicization

B. Thomassen

Turkish Law

S. Topal-Gökceli

Expeditions/Ukraine

T. Umrikhina

Hillforts

R. Welshman

Post-conflict

C. Westrik, S. Neuerburg13. Archäologentag

AUSGABE 54/III/2010

Archäologentag

F. Felten, C. Reinholdt, W. Wohlmayr

Befestigungen

T. Alusik

Villa urbana, Carnuntum

M. Behling

DressID-Projekt

I. Benda

Frühägäische Götter

F. Blakolmer

Kapitell in Graz

M. Christidis-Poulkou

Oriental./Minoische Götter

V. Dubcová

Textilproduktion

K. Gostenčnik

Spätantike Textilien

K. Grömer

Chronologie SH IIa

F. Höflmayer

Wasserversorgung/Syrakus

E. Kanitz

villa rustica/Brederis

J. Kopf

villa rustica/Neumarkt-Pfon

F. Lang et al.

Aula in Bruckneudorf

G. Kieweg-Vetters

Montanarchäologie/Stmk.

S. Klemm

Fibeln in Iuvavum

D. Knauseder

Zivilstadt/Carnuntum

A. Konecny

Kaiser als Pharao

G. Kremer

Partherdenkmal/Ephesos

A. Landskron

Porträts im KHM

M. Laubenberger

Hypokaustheizung

H. Lehar

Caracalla

H. Maier

Backöfen/Vindobona

M. Mosser

Prospektion in Oberlienz

F.M. Müller

Schönberg/Stmk.

K. Oberhofer

Alexandermosaik

T. Osada

Kulturvermittlung/Carnuntum

M. Pacher

Villa rustica/Oberndorf

A. Picker

Blatt und Blüte

K. Pruckner

Hadrianstempel/Ephesos

U. Quatember

Nachttöpfe

S. Radbauer, B. Petznek

Apollo - Augustus

M. Stütz

Reiter/Parthenonfries

E. Tanaka

Rotfig. Bauchlekythen

E. Trinkl

Tierlogogramme/Linear B

J. Weilhartner

Domitilla-Katakombe

N. Zimmermann

AUSGABE 53/XII/2009

FACEM

V. Gassner, K. Schaller

Tyrannen v. Ephesos

J. Fischer

Tonfries/Ephesos

C. Lang-Auinger

Spätantikes Ephesos

A. Pülz

Fundort Wien 2009

Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 52/IX/2009

Arch. Park Ephesos

M. Döring-Williams

Frauenberg

St. Karl

Sant Ypoelten

R. Risy

Mausoleum Bartringen

G. Kremer

AUSGABE 51/VI/2009

Magnesisches Tor

A. Sokolicek

Judenplatz, Wien

K. Adler-Wölfl

Am Hof, Wien

M. Brzakovic, A. Kupka, K. Lappé

Datenbank "lupa"

F. Harl, O. HarlÄgäische Bronzezeit

AUSGABE 50/III/2009

Vorwort

F. Blakolmer, C. Reinholdt, J. Weilhartner, G. Nightingale

Beziehungen Kretas

E. Alram

Kanalisation

M. Aufschnaiter

Kreuzbandschalen/Ägina

L. Berger

Thronraum/Knossos

F. Blakolmer

Ägäische Einflüsse

D. Doncheva

Unfreiheit u. Religion

J. Fischer

Ikonographie - Raum

U. Günkel-Maschek

Ägypten

P.W. Haider

Mann mit Lanze

S. Hiller

Kosmos als Kylix

S. Hiller

Steingefäße

F. Höflmayer

Ostägäis

B. Horejs

Architektur

D. Leiner

Handwerk

G. Nightingale

Das Thronen

B. Otto

Keramik/Ägina

K. Pruckner

Körperzeichen

K. Schaller

Livari/Südostkreta

N. Schlager

Sardinien/Mykene

L. Soro

Schwertkampf

R. Steinhübl

Mobilar

E. Wacha

Myk. Figurinen

I. Weber-Hiden

A. Evans/Linear B

J. Weilhartner

Josef Höfler

M. Zavadil

AUSGABE 49/XII/2008

Sog. Lukasgrab

A. Pülz

Velia 2008

V. Gassner

Palmyra 2008

A. Schmidt-Colinet

Wien 2008

Stadtarchäologie Wien

Magdalensberg 2008

E. Schindler Kaudelka

AUSGABE 48/IX/2008

DASV

P. Lochmann

Bassus Nymphaeum

E. Rathmayr

Alinda

P. Ruggendorfer

Phaistos Disc

Ch. Henke

AUSGABE 47/VI/2008

Römermuseum

M. Kronberger

Blindenführung

M. Teichmann

Malaria

A. Hassl

Stellenbörse

R. Karl12. Archäologentag

AUSGABE 46/III/2008

Vorwort

M. Meyer, V. Gassner

Expedition 1902

T. Alušík, J. Kostenec, A. Zäh

Geschneidertes Gewand

I. Benda-Weber

Nemeseum/Carnuntum

D. Boulasikis

Phallos-Steine

E. Christof

Wandmalerei/Carnuntum

C.-M. Girisch

Beinfunde

K. Gostenčnik, F. Lang

Archäologie/Steiermark

B. Hebert, E. Pochmarski, U. Steinklauber

Pottenbrunn

E. Hölbling

Bewässerung

E. Kanitz

Werkstätten/Iuvavum

D. Knauseder

CSIR

G. Kremer

Heroon von Trysa

A. Landskron

CVA

C. Lang-Auinger

Villa/Debant

F.M. Müller

Amazonen

T. Osada

Glas/Palmyra

R. Ployer

Hydreion/Ephesos

U. Quatember

Informationssysteme

K. Schaller, Ch. Uhlir

Österreich-Kreta

N. Schlager

Kultplatz 1/Velia

D. Svoboda

Neue Medien

E. Trinkl

Pausanias-Ägina

J. Weilhartner

Spiegel, KHM

K. Zhuber-Okrog

Domitilla-Katakombe

N. Zimmermann

AUSGABE 45/XII/2007

Initiative Österr.

ArchäologInnen

B. Kainrath

Inclusion Fluids

W. Prochaska, S.M. Grillo, P. Ruggendorfer

Fugenmörtel

D. Boulasikis

Velia 2007

V. Gassner

Römische Villen

B. Schrettle

Michaelerplatz

Stadtarchäologie WienHanghaus 2 von Ephesos

AUSGABE 44/IX/2007

Hanghaus 2

H. Thür

Möbel

E. Rathmayr

Küchen

L. Rembart

Räume 14 + 19

G. Zluwa

Triklinium SR 24

A. Nordmeyer, A. Sommer

Raum 26

J. Reuckl

Marmorsaal I

S. Stökl

Marmorsaal II

S. Swientek

Raum 31b

M. Tschannerl

basilica privata

M. Gessl

Kurzzitate

AUSGABE 43/VI/2007

Sonnenuhr

C. Lang-Auinger

Faschistisches Rom

U. Quatember

C. Praschniker

G. Wlach

Nymphen

E. TrinklStadien-Siege-Skandale

AUSGABE 42/III/2007

Zum Geleit

H. Szemethy

Athleten

M. Röder

Recht & Ordnung

S. Seitschek

Skandale

S. Seitschek

Kampfsportarten

A. Nordmeyer

Pentathlon

L. Bäumel

Hippische Agone

M. Weisenhorn

Preise

M. Röder

Fans

K. Preindl

Berlin 1936

F. Mayr

Bibliographie

AUSGABE 41/XII/2006

Satyr, Greifswald

R. Attula

Carnuntum

U. Lohner

Velia 2006

V. Gassner

F. Schachermeyr

M. Pesditschek

Fundort Wien

Stadtarchäologie Wien

AUSGABE 40/IX/2006

Ägina, Keramik

G. Klebinder-Gauß

Kyrene, Agora

A. Giudice

Kyrene, Gymnasium

A. Giudice

Ernst Sellin

F. Schipper11. Archäologentag

AUSGABE 39/VI/2006

Archäologentag

E. Walde

Prähist. Defensivarchitektur

T. Alušík

Stadtmauer/Aguntum

M. Auer

Keramik/Ägina

L. Berger

Mittelhell. Bildkunst

F. Blakolmer

Ferrum Noricum

B. Cech, H. Preßlinger, G. Walach

Wandmalerei/Virunum

I. Dörfler

Lukaner in Velia?

V. Gassner

Übergangsriten, Herakleia

V. Gertl

Basis v. Sorrent

M. Grossmann

Greif

P.W. Haider

Steirische Archive

B. Hebert

Anton Roschmann

M. Huber

Schützengasse, Wien

S. Jaeger-Wersonig

Steindenkmäler, Carnuntum

G. Kremer

archaeologieforum.at

K.R. Krierer

Model, Ephesos

C. Lang-Auinger

Türme auf Kreta

E. Mlinar

Zivilstadt, Vindobona

M. Mosser

Daunische Siedlungsbefunde

F.M. Müller

Ostgiebel, Olympia

T. Osada

Werkstatt & Muster

G. Plattner

Akropolis, Ägina

E. Pollhammer

Straßenbrunnen, Ephesos

U. Quatember

Gräbertypologie, Daunien

J. Rückl

Kieselpflasterung, Daunien

E. Schemel

Nymphen - Mänaden

G. Schmidhuber

Tempel, Kalapodi

V. Sossau

Röm. Brixner Becken

A. Waldner

Aigina und Athen

J. Weilhartner

Ringhallentempel

M. Weissl

Österreichischer Archäologenverband

AUSGABE 38/III/2006

Antikensammlung, KHM

K. Gschwantler

Bergbau, Montafon

R. Krause

Gewandstatue

A. Landskron

Weinbau

F. Brein

AUSGABE 37/XII/2005

NASCA Ceramics

H. Mara, N. Hecht

Palmyra 2005

A. Schmidt-Colinet

Velia 2005

V. Gassner

Fundort Wien

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 36/IX/2005

Kulturgüter im Irak

F. Deblauwe

Goldappliken, Artemision

A.M. Pülz

Goldappliken, Technologie

B. Bühler

Nymphäum von Apamea/Syrien

A. Schmidt-Colinet, U. Hess

Ägypten/Griechenland/Rom

B. Gessler-LöhrNeue Zeiten-Neue Sitten

AUSGABE 35/VI/2005

Kolloquium Wien 2005

M. Meyer

Asinii Nicomachi

F. Chausson

Lampen

A. Giuliani

Italiker

F. Kirbihler

Artefactual/Artificial

J. Poblome, Ph. Bes, V. Lauwers

Ti. Claudius Aristion

U. Quatember

Keramik 1.Jh. v.Chr.

Ch. Rogl

Schwarzweißmosaike

V. Scheibelreiter

Bad-Gymnasium-Komplexe

M. Steskal

Imperial cult/Pisidia

P. Talloen

Münzen/Pergamon

B. Weisser

Wandmalerei/Ephesos

N. Zimmermann

AUSGABE 34/III/2005

3D-Vision in Archaeology

H. Mara, R. Sablatnig

Velia 2004

V. Gassner

Aelium Cetium

R. Risy, P. Scherrer, E. Trinkl

Archäologie in Serbien

U. Brandl

AUSGABE 33/XII/2004

Wandmalerei, Magdalensberg

K. Gostenčnik

Herakles i. Aguntum

St. Karwiese

Vindobona-CD

M. Klein, M. Kronberger, M. Mosser

Geschichte

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 32/IX/2004

Peter Cornelius

L. Krempel

Durchblick-Panorama

Ch. Tschaikner

Ares Borghese, KHM

T. Friedl

Akropolis/Lindos

K. Rieger

AUSGABE 31/VI/2004

Mark Aurel/Carnuntum

F. Humer

Partherdenkmal, KHM

W. Oberleitner

GIS / Marienkirche

Ch. Kurtze

Archäologie/Bodensee

A. Troll, J. Hald

Besiedlungsstruktur

N. Alber

AUSGABE 30/III/2004

Spurensicherung

C. Holtorf

Gewebte Erinnerungen

G. Rapp, H. Rapp

Velia 2003

V. Gassner, A. Sokolicek

Keramikchronologie/ Velia

M. Trapichler

Kulturgeologie

W. Vetters

Klimakatastrophe

W. Vetters, H. Zabehlicky10. Österr. ArchäologentagZum Geleit

AUSGABE 29/XII/2003

G. SchwarzErscheinungsfenster

T. AlušíkArchitektur/Tavium

E. ChristofMilitärlager/Virunum

M. Doneus, Ch. Gugl, R. JernejAsyl von Ephesos

R. FleischerNekropole/Virunum

G. FuchsMagdalensberg

F. GlaserNeuaufstellung KHM

K. GschwantlerHermenmal

R. HanslmayrStein-Relief-Inschrift

Ch. Hemmers, St. TraxlerMarmorgemagerte Keramik

S. Jäger-WersonigAgäer in Italien

R. JungAntikensammlung R. Knabl

St. KarlMarmorsteinbrüche/

Ephesos

K. KollerPartherdenkmal

A. LandskronHibernia

S. LausBrustschmuck d. Kybele

F.M. MüllerSiphnierschatzhaus

T. OsadaPompeii, Regio VII

L. Pedroni, D. Feil, B. TasserOst und West

G. PlattnerGrabbezirk v. Faschendorf

J. Polleres, W. ArtnerBärinnen in Brauron

M. PoulkouRomanisierung im Comics

U. Quatember, K.R. KriererLykische Schrift

M. SeyerTextilverarbeitung

E. TrinklAltäre/Artemision

M. Weißl

AUSGABE 28/IX/2003

Pottery/Maussolleion

L.E. Vaag, V. Nørskov, J. Lund

Goldappliken/Artemision

A.M. Pülz

Peion/Ephesos

S. Karwiese

Geländerekonstruktion/

Wien

R. Gietl, M. Kronberger, M. Mosser

Schutzanstrich/

Amphoren

C. Sehnal

AUSGABE 27/VI/2003

Bronzewerkstätte/

Artemision

G. Klebinder-Gauß

Ubi-erat-lupa

F. Harl, K. Schaller

Diateichisma

A. Sokolicek

Archäologie in Oberösterreich

S. Lehner

Science Week 2003

M. Holzner, A. Vacek

AUSGABE 26/III/2003

Jupiter-Dolichenus Tafel, KHM

P. Pingitzer

Marmorrelief mit Säge

M. Büyükkolanci, E. Trinkl

Tonlampen/Ephesos

A. Giuliani

'Toilet Room', Knossos

M. Aufschnaiter

Karthago - Spiegelgrund

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 25/XII/2002

Colonia Ulpia Traiana

U. Brandl, F. Diessenbacher

Velia 2002

V. Gassner, A. Sokolicek, M. Trapichler

Torbau/Limyra

P. Ruggendorfer

Kirche/Limyra

A. Pülz

Amazonenrelief/Wien

M. Weißl

Boische Grabbauten

M. Mosser

AUSGABE 24/IX/2002

Erlebnis Altertum,

Science Week 2002

M. Holzner, M. Ladurner

Legionslager Vindobona,

Science Week 2002

M. Mosser

Griechen & Fremde,

Science Week 2002

S. Fürlinger

TS aus Cales

L. Pedroni, B. Tasser

Koren

J. Eitler

Koptische Ärmelborte

Ch. Pflegerl

AUSGABE 23/VI/2002

Inscriptions of Aphrodisias

G. Bodard, Ch. Roueché

Griechisches Knossos

E. Mlinar

Carnuntumausstellung, Brixen

E. Wierer

Spiegel-Corpus Schweiz

I. Jucker, Rez. F. Brein

AUSGABE 22/III/2002

Glasbecher, IKA

S. Jäger-Wersonig

Glas-Konservierung

K. Herold

Partherdenkmal

A. Landskron

Spittelwiese, Linz

R. Ployer

AUSGABE 21/XII/2001

Marmorkleinplastik in Aquileia

E. Christof

Frühchristliche Ampullen

S. Ladstätter, A. Pülz

Velia 2001

V. Gassner

Fundort Wien 4/2001

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 20/IX/2001

Keramik-Restaurierung

K. Herold

Augenschale

B. Kratzmüller

Lekythos

B. Kratzmüller

Loutrophoros

B. Kratzmüller

Schwarzfirnis-Dekor

E. Trinkl

Palmyra 2001

A. Schmidt-Colinet

Kopie & Fälschung

Ch. Gastgeber

AUSGABE 19/VI/2001

Grabbezirk von Faschendorf

J. Polleres

Von Virunum nach Iuvavum

Ch. Gugl

Hemmaberg / Kärnten

S. Ladstätter

Murale - Project

M. Kampel, R. Sablatnik

Ägypten in bunten Bildern

U. Quatember

AUSGABE 18/III/2001

Nemesis in Virunum

Ch. Gugl

Tafel- & Qualitätswein

H. Liko

Mantik in Mantineia

A. Hupfloher

Artemision / Ephesos

M. Weißl

Hellenist. Keramik / Ephesos

Ch. Rogl

Frühbyzantinische Münzen

M.A. Metlich

Brustkreuze

W. Hahn

AUSGABE 17/XII/2000

Amphitheater/Virunum

R. Jernej

Geschichte des IKA

V. Gassner

Homer & Entenhausen

U. Quatember

Archäologie & Computer

W. Börner

Fundort Wien

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

AUSGABE 16/IX/2000

Zeugma

M. Büyükkolanci

Dach für Ephesos

F. Krinzinger

Theater v. Perge

A. Öztürk

Priester in Sparta

A. Hupfloher

AUSGABE 15/VI/2000

Nochmals Vota

St. Karwiese

Mesopotamiens Bootsgott

B. Stöcklhuber

Arge Arch

F. Schipper

Digitale Bilddokumentation

K. Koller

Torrenova, Sizilien

E. Kislinger

Unterwasserarchäologie

Ch. Stradal, C. Dworsky

Sudan

M. ZachAltmodische Archäologie

AUSGABE 14/III/2000

Festschrift f. F. Brein

Tabula Gratulatoria

Schriftenverzeichnis

F. Brein 1964-1999

Zusammenst. M. Bodzenta

Gewicht aus Ephesos

M. Aurenhammer

Schlüssel, Schloß & Knoten

H. Bannert

Min. "Zahnornament"

F. Blakolmer

Vounous-Modell

L. Dollhofer, K. Schaller

Anheben d. Gewandsaumes

U. Eisenmenger

Keramik aus Eretria

R. Fenzl

Stele aus Grottaferrata

T. Friedl

"Da Hiib"

A. Gasser

Oinotrer in Elea?

V. Gassner

Flora & Fauna in Pleuron

W. Gerdenitsch, K. Mazzucco

Neues aus Rom

W. Greiner

Hermerot aus Ephesos

R. Hanslmayer

Zwei Wiener Ostraka

H. Harrauer

Feder & Tinte

S. Jilek

List - Hitler - Carnuntum

M. Kandler

Neokorie f. Macrinus

St. Karwiese

Buntgesteine in Ephesos

K. Koller

Auslosung im Sport

B. Kratzmüller

Kopfgefäß aus Ephesos

C. Lang-Auinger

Sphinx von Fischlham

M. Pippal

St. Martin / Raab

E. Pochmarski, M. Pochmarski-Nagele

Bronzelöwe aus Lousoi

Ch. Schauer

Eber - Heros

P. Scherrer

Kyklop. Bauten / Ostkreta

N. Schlager

Weinlese in Palmyra

A. Schmidt-Colinet

Römische Juristen

R. Seliger

Kranz - Krone - Korb

E. Specht

Datierung d. Propyläenkore

M. Steskal

FS O. Benndorf

H. Szemethy (Hrsg.)

Basileia in Ephesos?

H. Thür

Rocken & Spindel

E. Trinkl

Ägäische Gewandweihen

E. Trnka

Herakles / African Red Slip

P. Turnovsky

Deckenfresko in Enns

E. Walde

Corocotta

E. Weber

Ökonomie d. Archäologie

W. Weigel

Festung Elaos

M. Weißl

Graffiti / Bruckneudorf

H. Zabehlicky

AUSGABE 13/XII/99

Tell Arbid, Syria

G.J. Selz

Ephesische Laren

U. Quatember

Welser Gräberfeld

S. Jäger-Wersonig

Arthur Project

F. Niccolucci

Arch. Sammlung II

F. Brein (Hrsg.)

AUSGABE 12/IX/99

Warrior tomb, Egypt

I. Forstner-Müller

Akropolis, Athen

F. Ruppenstein, W. Gauß

Amymone auf Mosaiken

A. Kankeleit

Römische Mosaike

V. Scheibelreiter

Palmyra 1999

A. Schmidt-Colinet

Barbanera. Besprechung

S. Altekamp

AUSGABE 11/VI/99

Ausgabe 11/VI/99

8. Österr. ArchäologentagZum Geleit

F. Blakolmer, H.D. SzemethyStuckreliefs

F. BlakolmerStadtmauern von Velia

V. GassnerHeiligtum in Byblos

P.W. HaiderZeus in Ephesos

E. TrinklPartherdenkmal v. Ephesos

A. LandskronKleinasiat. Theaterfriese

H.S. AlanyaliKeramik aus Xanthos

B. Yener-MarksteinerPeloponnesische Reliefbecher

Ch. RoglLampen aus Aigeira

Th. HagnLagertor v. Vindobona

M. MosserAuxiliarkastell/Carnuntum

W. Müller, U. ZimmermannBadegebäude in Altheim

K.A. EbetshuberBad in Klosterneuburg

M. PhilippVilla von Höflein

R. KastlerNorische Grabbautypen

G. KremerFranz Miltner

K.R. KriererRechtsarchäologie

R. SelingerKulturgüterschutz

H. Szemethy

AUSGABE 10/III/99

Apasas - Ayasuluk

M. Büyükkolanci

Mythisches Ephesos

M. Steskal

Seleukeia Sidera

E. Lafli

Archäometrie in Velia/Italien

V. Gassner, R. Sauer

100 Jahre ÖAI

ÖAI (Hrsg.)

AUSGABE 9/XII/98

Zoomorphes Dekor

L. Dollhofer

Recycling misfired pottery

Poblome, Schlitz & Degryse

Die römische Palastvilla

H. Zabehlicky

Stadtarchäologie Wien

Wr. Stadtarchäologie

Ancient DNA

J. KiesslichÄgäische Bronzezeit

AUSGABE 8/IX/98

Vorwort

F. Blakolmer

Bulgarien & Nordgriechenl.

I. Schlor

Keramik aus Pheneos

G. Erath

Grazer Institutssammlung

M. Lehner

Halbrosetten / Federfächer

M. Weißl

Hoheitszeichen

B. Otto

Hogarth's Zakro Sealing No.130

N. Schlager

Die Larnax von Episkopi

F. Lang

Hundedarstellungen

B. Schlag

Ägyptische Quellen

P. W. Haider

Der Friedhof von Elateia

A. E. Bächle

Mykenische Perlen

G. Nightingale

Frauen- und Männertracht

E. Trnka

Die Akropolis von Athen

W. Gauß

ásty und pólis

J. Weilhartner

Farbe in der ägäischen Bildkunst

F. Blakolmer

AUSGABE 7/VI/98

Prähist. Ephesos

M. Büyükkolanci

Ephes. Kaiserpriester

H. Thür

Hadrians Innenpolitik

G. Plattner

Red Slip Ware

J. Poblome

Sigillatadepot / St. Pölten

Ch. Riegler

Fundort unbekannt

H.D. Szemethy

AUSGABE 6/III/98

Ephesos 1997

St. Karwiese

Plataiai - Survey

A. Konecny

"Satyrisches"

M.E. Großmann

Augentäuschungen

G. Vetters

Keramik und Laser

M. Kampel & Ch. Liska

AUSGABE 5/XII/97

Ephesian Water System

D. Crouch & Ch. Ortloff

Digitaler Stadtplan

St. Klotz & Ch. Schirmer

Mautern - Favianis

St. Groh

Kirchberg / Kremsmünster

R. Risy

Emanuel Löwy

F. Brein (Hrsg.)Metropole Ephesos

AUSGABE 4/VIII/97

Resumée 1996

St. Karwiese et al.

Hist. Topographie

P. Scherrer

Artemision of Ephesus

A. Bammer

Der Hafen von Ephesos

H. Zabehlicky

Inschriften von Ephesos

D. Knibbe

Das Große Theater

I. Ataç

Latrinengerüch(t)e

U. Outschar - H. Thür

Nekropolen

E. Trinkl

Rouge et noir

S. Zabehlicky

Ephesos-Gesamtplan

Stand 1997

Bibliographie 1988-97

M. Bodzenta

AUSGABE 3/V/97

Kentauromachie

H. S. Alanyali

Grabbauten Noricums

G. Kremer

Puer Ludens

W. Reiter

Bronzezeitl. Tätowierung

K. Schaller

AUSGABE 2/II/97

Kyprische Vasen

F. Brein (Hrsg.)

Choenkännchen

E. Eberwein

Römische Landgüter

K. A. Heinzl

Geophys. Prospektion

W. Neubauer - P. Melichar

Frühbyz. Bauornamentik

A. Pülz

AUSGABE 1/XI/96

Archäolog. Sammlung

F. Brein

Täfelung des Serapeions

K. Koller

Synoris und Apene

B. Kratzmüller

Zeustempel zu Olympia

H. Nödl

Spindel, Spinnwirtel & Rocken

E. Trinkl

Alexander the Great-Era Tomb Will Soon Reveal Its Secrets

As archaeologists continue to clear dirt and stone slabs from the entrance of a huge tomb in Greece, excitement is building over what excavators may find inside.

The monumental burial complex — which dates back to the fourth century B.C., during the era of Alexander the Great — is enclosed by a marble wall that runs 1,600 feet (490 meters) around the perimeter. It has been quietly revealed over the last two years, during excavations at the Kasta Hill site in ancient Amphipolis in the Macedonian region of Greece.

Excavators recently unearthed the grand arched entrance to the tomb, guarded by two broken but intricately carved sphinxes. Read more.

The Fouad Debbas Collection: assessment and digitisation of a precious private collection. Photographs from Maison Bonfils (1867-1910s), Beirut, Lebanon

British Library Endangered Archives Programme

The aim of this project is to clean, list, index, catalogue and digitise a collection of 3,000 photographs produced in the Middle East by the Maison Bonfils, from 1867 to the 1910s.

The 3,000 items consist of albumen prints gathered in albums and portfolios, glass plates, stereos, cabinet cards and cartes de visite. They are part of the general Fouad Debbas Collection, which contains more than 40,000 photographs. The objective is to undertake a survey, and increase access to and visibility of this most valuable and endangered collection.

The Fouad Debbas Bonfils collection is the most extensive, varied and richest photographic collection produced in the Levant at the end of the Ottoman period. It is in fact one of the very few photographic collections produced in Beirut from the late Ottoman period which are still preserved.

Established in 1867 in Beirut, the Bonfils house set out the first photographic studio in Beirut and established photography as a business. As such Mr Bonfils, his wife Lydie, (apparently the first woman photographer of the whole area at that time) and children, all succeeded in capturing a region of immense physical beauty (the landscape photos of Beirut and Baalbeck), of varied ethnic composition (various portraits), and of rapid socio-economic change, at a crucial moment of the region’s history. The Bonfils Debbas collection is clearly an invaluable document registering the history of a region at a crucial crossroads in the wake of great historical upheaval which was about to sweep the region and bring about the Modern Middle East as we know it...

VIEW FILES FROM THIS PROJECT

The catalogue is available here.

Excerpts from the martydom tale of Goharine &c. in the Armenian synaxarion (with a talking decapitated head!)

As I’ve done before (see also here), here are a few sentences from the Armenian synaxarion together with Bayan’s French translation. I’ve made a few notices of the Armenian vocabulary, too, ad usum scholarum. The story here (for 24 Hrotic’/30 July) is the martyrdom of Goharine and her brothers (nothing in BHO; summary in English here), set, it seems, in the twelfth century. The PO text (21: 795-799) and FT is here.

795

հայրն իւրեանց Դաւիթ գերեալ ի Տաճկաց որ եւ դարձուցին զնա ի կրօնս իւրեանց, եւ զանդրանիկ որդի նորա։

- գերեալ ptcp գերեմ, -եցի to take prisoner, capture

- Տաճիկ, -ճկաց Arab; Turk

- դարձուցանեմ, -ուցի to turn, convert

- կրօն, -նից religion; custom; way of life; sect

- անդրանիկ, -կաց oldest, first-born

Leur père David fut emmené captif par les Musulmans qui le convertirent à leur religion ainsi que son fils aîné.

************

796

Իսկ մայրն իւրեանց հաստատուն եկաց ի հաւատսն որ ի Քրիստոս, եւ բարեպաշտութեամբ սնոյց զորդիս իւր.

- հաստատուն firm, solid, constant

- եկաց 3s aor of կամ to stand (Meillet § 112)

- հաւատ, -ոյ, -ք, -տոց faith, belief, creed

- բարեպաշտութիւն piety, religion

- սնոյց 3s aor of սնուցանեմ, -ցի, սնո՛ to nourish, instruct (see the end of the post for more on this verb)

Mais leur mère demeura ferme dans sa foi au Christ, et éleva pieusement ses enfants;

************

եւ վասն արիութեանն իւրեանց զինուորեցան բռնաւորին Տաճկաց Ալի Բասանայ, յազգէ Դանշմանացն որ տիրէր Սեբաստիոյ եւ կողմանցն Պոնտոսի,

- արիութիւն bravery, courage (արի brave, courageous)

- զինուորեցան 3pl aor mid/pas զինուորեմ, -եցի to enlist, maintain soldiers (so in the mid/pas, to be enlisted in the army)

- բռնաւոր violent; tyrant

- ազգ, -աց nation, people

- տիրէր 3s impf տիրեմ, -եցի to rule, seize, conquer

- կողմն, -մանաց quarter, country, region

ceux-ci à cause de leur courage s’enrôlèrent dans l’armée du tyran musulman Ali Bassan, de la race des Danishmends, qui régnait à Sébaste et sur les contrées du Pont;

************

այր գազանաբարոյ եւ արիւնախանձ մոլեալ ընդդէմ քրիստոնէից։

- գազանաբարոյ fierce, savage (գազան beast)

- արիւնախանձ bloodthirsty, cruel (արիւն, արեանց blood)

- մոլեալ ptcp of մոլեմ, -եցի to drive made (so here, raging, furious)

- ընդդէմ against

homme d’un naturel bestial, assoiffé de sang, et fou furieux contre les chrétiens.

************

Նոքա որդիք են տաճկի եւ թողեալ զօրէնս մեր կան քրիստոնէութեամբ, գարշին ի կերակրոց մերոց, եւ ոչ կան յաղօթս ընդ մեզ։

- թողում, թողի to abandon, give up

- օրէնք, օրինաց faith, religion

- կան (2x) 3pl pres կամ, կացի to be, exist, live, remain, stand

- գարշիմ, -եցայ to detest, hate, abhor

- կերակուր, -կրոց food

- աղօթք, -թից prayer

Ce sont les enfants d’un musulman, qui ont abandonné notre religion, vivent en chrétiens, répugnent à nos mets et ne prient point avec nous.

************

797

Ռատիոս գնաց ի վանքն եւ եղել կրօնաւոր։

- գնաց 3s aor. ind. գնամ, գնացի to go

- վանք convent, monastery

- եղել 3s aor եղանիմ to become

- կրօնաւոր monk (< կրօն, -ք, -նից religion, faith; religious order, monastic life)

Ratios se retira dans un couvent et se fit religieux.

************

…հրամայեաց փորել զերկիր եւ թաղել զԳոհարինէ մինչեւ ի մէջսն, եւ նետաձիգ լինել ի նա ամենայն բազմութիւնն։

- հրամայեաց 3s aor հրամայեմ, -եցի to command

- փորել inf փորեմ, -եցի to dig

- թաղել inf թաղեմ, -եցի to bury

- մէջ, միջոյ, -ով (pl.) middle > waist

- նետաձիգ լինել to shoot an arrow (cf. նետ, -ից arrow, shaft, dart)

- բազմութիւն crowd, multitude

…il ordonna de creuser la terre et d’y enterrer Gohariné jusqu’à la taille, et commanda à toute la foule de lui lancer dex flèches.

************

798

Եւ բարկացեալ անօրէնն հրամայեաց զԳոհարինէ հեղձամղձուկ առնել ի ջուրն հեղեղատին. եւ զՏունկիոս եւ զԾամիդէս ածել զառաջեաւ, եւ զՌատիոս պրկել փոկովք եւ հարկանել։

- բարկացեալ angry, in a rage (cf. բարկանամ, -ացայ to be angry)

- անօրէն unjust, wicked

- հեղձամղձուկ suffocated, choked (adj.)

- առնել inf առնեմ, արարի to make, cause (w/ prev. and foll. words: to drown)

- ջուր, ջրոյ water

- հեղեղատ, -աց torrent (cf. հեղեղ, -աց torrent, flood)

- ածել inf ածեմ, ածի to fetch, carry, bring

- զառաջեաւ before, in front (adv.)

- պրկել inf պրկեմ, -եցի to bind

- փոկ, -ոց/-աց leather thong, strap

- հարկանել inf հարկանեմ, հարի to beat, strike

L’infidèle, irrité, ordonna de noyer Gohariné dans les eaux du torrent et d’introduire en sa présence Tounkios, Dsamidès, puis d’enserrer fortement Ratios dans des lanières et de le frapper.

************

եթէ թողուս մեզ կեալ քրիստինէութեամբ, եւ քեզ ծառայեսցուք միամտութեամբ, ապա թէ ոչ այլ իրք մի՛ հարցաներ ընդ մեզ. քրիստոնէայք եմք, զոր ինչ առնելոց ես արա՛։

- թողուս 2s pres թողում, թողի to let, leave, allow

- կեալ inf կեամ to live

- ծառայեսցուք 1p aor ծառայեմ, -եցի to serve, wait upon

- միամտութիւն sincerity, fidelity, simplicity

- իր, -ի, -աց thing, affair

- հարցաներ 2s imv հարցանեմ, -ցի to ask

- եմք 1p pres եմ to be

- առնելոց ptcp gen.pl. [NB -եալ > -ելV] առնեմ, արարի to do

- ես 2s pres եմ to be

- արա՛ 2s imv առնեմ, արարի to do

…si tu nous laisses vivre en chrétiens, nous te servirons fidèlement; dans le cas contraire, ne nous fais plus de questions: nous sommes chrétiens; fais ce que tu as à faire.

************

799

Եւ տարեալ ի տեղի կատարմանն հատին զգլուխ երանելոյն Ռատիոսի։ Եւ հատեալ գլուխն խօսէր եւ քաջալերէր զեղբարսն մի՛ երկնչել ի մահուանէ։

- տարեալ ptcp տանիմ, տարայ to lead [NB -ն- in pres, -ր- in aor]

- տեղի, -ղւոյ, -ղեաց place, spot, site

- կատարումն end, death, completion (here gen.sg.; see Meillet § 56 for nouns in -մն)

- հատին 3p aor հատանեմ, հատի to cut

- գլուխ, գլխոց head

- երանեալ blessed, happy [again NB -եալ > -ելV] (cf. in Ps 1:1, Երանեալ է այր որ ո՛չ գնաց ՛ի խորհուրդս ամպարշտաց, but the Beatitudes have a different, but related adjective: Երանի́ աղքատաց հոգւով, etc.)

- հատեալ ptcp հատանեմ, հատի to cut

- խօսէր 3s impf խօսիմ, -եցայ to speak

- քաջալերէր 3s impf քաշալերեմ, -եցի to encourage, embolden

- եղբայր, եղբաւր, եղբարց brother (Meillet § 57b)

- երկնչել inf երկնչիմ, -կեայ, -կի՛ր to fear

- մահ, մահու/մահուան death (Meillet § 59f)

Les ayant menés au lieu de l’exécution, ils tranchèrent la tête au bienheureux Ratios. Mais la tête tranchée parla à ses frères et les encouragea à ne point craindre la mort.

************

On the form սնոյց. The 3s aor ends in -ոյց, the 1s being -ուցի. For the alternation ոյ/ու (see Meillet, p. 18; Godel §2.222), cf. լոյս light, with gen/dat/abl լուսոյ; that is, -ոյ- in closed syllable, -ու- in open syllable.

Here are a few more occurrences of the form (also with the imper in Ex 2:9), with the Greek for the biblical texts:

Ex 2:9 եւ ասէ ցնա դուստրն փարաւոնի. ա́ռ զմանուկդ, եւ սնո́ ինձ զդա. եւ ես տաց քեզ զվարձս քո։ Եւ ա́ռ կինն զմանուկն՝ եւ սնոյց զնա։ εἶπεν δὲ πρὸς αὐτὴν ἡ ϑυγάτηρ Φαραω Διατήρησόν μοι τὸ παιδίον τοῦτο καὶ ϑήλασόν μοι αὐτό, ἐγὼ δὲ δώσω σοι τὸν μισϑόν. ἔλαβεν δὲ ἡ γυνὴ τὸ παιδίον καὶ ἐϑήλαζεν αὐτό.

Dt 1:31 զի սնո́յց զքեզ տ(է)ր ա(ստուա)ծ քո, ո(ր)պ(էս) սնուցանիցէ ոք զորդի իւր ὡς ἐτροϕοϕόρησέν σε κύριος ὁ ϑεός σου, ὡς εἴ τις τροϕοϕορήσει ἄνϑρωπος τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ

1Sam 1:23 Եւ նստա́ւ կինն եւ սնո́յց զորդին իւր՝ մինչեւ հատոյց զնա ՛ի ստենէ։ καὶ ἐκάϑισεν ἡ γυνὴ καὶ ἐϑήλασεν τὸν υἱὸν αὐτῆς, ἕως ἂν ἀπογαλακτίσῃ αὐτόν.

Ps 22:2 եւ առ ջուրս հանգստեան սնոյց զիս։ ἐπὶ ὕδατος ἀναπαύσεως ἐξέϑρεψέν με

Acts 7:21 եւ յընկեցիկն առնել զնա՝ եբարձ զնա դուստրն փառաւոնի, եւ սնոյց զնա ի́ւր յորդեգիրս։ ἐκτεϑέντος δὲ αὐτοῦ ἀνείλατο αὐτὸν ἡ ϑυγάτηρ Φαραὼ καὶ ἀνεϑρέψατο αὐτὸν ἑαυτῇ εἰς υἱόν.

Agat. § 37 եւ մերձաւորեալ զնա սնոյց դայեկօք երկիւղիւն Քրիստոսի. Thomson, p. 53: “And he was brought up by his tutors [lit. he (i.e. an unnamed person), having adopted him, raised him with tutors (n. on p. 458)] in the fear of Christ.”

Amphipolis Tomb Possibly Looted in Antiquity? I am Officially Confused!

In my precaffeinated minutes this a.m. I was jarred awake by a typically hyperbolating Daily Mail headline proclaiming: Game over for Greece’s mystery grave: Tomb raiders plundered site in antiquity – dashing hopes of finding artefacts dating back to Alexander the Great’s reign. Inter alia, a number of times the mantra was repeated, but here’s one excerpt:

[...] Experts had partially investigated the antechamber of the tomb at the Kasta Tumulus site near ancient Amphipolis in Macedonia, Greece, and uncovered a marble wall concealing one or more inner chambers.

They said that a hole in the decorated wall and signs of forced entry indicate it was plundered, but excavations will continue for weeks to make sure. [...]

- via: Game over for Greece’s mystery grave: Tomb raiders plundered site in antiquity – dashing hopes of finding artefacts dating back to Alexander the Great’s reign (Daily Mail)

Now before I deal with the (actually reasonably good evidence) for the claim, I want to sort of ‘run through’ the course of the excavation (with photos from the Ministry of Culture, in the order they’ve appeared at their site), which led me to ask some questions about this tomb that I hope someone can answer. First, here’s an early image that made the rounds of various press agencies, which shows the first revelation of the “sphinxes”. I want folks to notice that the outer wall is ‘continuous’. We can also clearly see the archway with the “sphinxes” and a wall that was built in front of them.

The blocks in front were removed …

… and we were presented with a photo of the “sphinxes” … notice there is much dirt behind them. Some of us were idly speculating that there was a hole of some sort behind the “sphinx” on the right, but in hindsight it struck me that there really wasn’t enough room for someone to get behind the “sphinx” to dig like that.

Next, they began clearing the ‘entrance’ to the tomb and we heard, inter alia, of a mosaic pavement, but alas, we never did see a photo of same. This would suggest that they had cleared right to the ‘floor’ of the entrance, but I’m not sure that is the case. The photos from the entrance clearing did reveal some nice (painted) details, however. Ecce the initial views (we posted these already):

And now:

Then they were inside the vestibule:

This photo gives an idea of the soil filling the vestible (i.e. in the space behind the “sphinxes”. There clearly was a lot to be removed:

There’s a photo of the dirt having been cleared from behind the “sphinxes”:

Looking through that you can possible see a trace of the photo that’s causing “disappointment”:

If you look in the upper left, you’ll see the small (40cm x 60cm, according to various reports) hole which possibly provided access to the inside. You can also see the level of the dirt inside and — I’m assuming, from the white shading there –the level the dirt was at. The hole (if it is a hole going all the way through) is large enough for a small person to get through. But how did they get in to dig that hole? The vestibule has a barrel-vaulted stone roof, it appears, so something horizontal from the front? It really doesn’t make sense to me. If it was plundered in antiquity, I doubt they went ‘through the front door’.

Then again, and this is why I have questions, why is this vestibule filled to the top with dirt? Is this a typical Macedonian practice (I honestly don’t know). Or was this done later in antiquity, perhaps around the time of the ‘beheading of the sphinxes’? Even then, however, why was it all blocked off with those massive blocks? Done at the time of burial or later in antiquity? If at the time of burial, wouldn’t they have used better dressed stones? And when/why did they fill the space between the blocks and the “sphinxes” with dirt? Was all this meant to be ‘hidden’ or was it once open for passers by to see?

Folks wondering about the ‘latest’ can turn to this a.m.’s Greek version of Kathimerini, where it is revealed that the next few days will be spent protecting the paint and shoring up walls and the like:

- Αμφίπολη: Προτεραιότητα η συντήρηση των ευρημάτων (Kathimerini)

… and here are the Ministry Press Releases whence came the above photos (they have other titles, but the MoC’s website has things set up somewhat unconventionally and it’s an incredibly slow site to access):

- Δελτία Τύπου (Aug 24)

- Δελτία Τύπου (Aug 25)

- Δελτία Τύπου (Aug 21)

Some of our previous coverage:

- August 21 at Amphipolis ~ From the Ministry of Culture

- Quick Amphipolis Update: Significant Fragments (August 20)

- Brace Yourselves: News From Amphipolis is Coming …

Colosseum – Arkkitehtuuriltaan Täydellinen Rakennus Julmien Huvien Näyttämönä Osa. 1

Opiskellessani kulttuurihistoriaa Turun Yliopistossa valitsin erään tutkielmani aiheeksi Colosseumin, jonka aion nyt julkaista blogissani kaksiosaisena. Colosseum ja sen historia on kiehtonut minua aina. En unohda koskaan sitä hetkeä kun ensi kerran näin tämän jättiläismäisen, kuuluisan monumentin. Colosseumilla kävellessäni tunsin astuvani sisään muinaiseen antiikin maailmaan. Mieleeni nousi paljon kysymyksiä : miten Colosseum on rakennettu ja keitä sitä olivat rakentamassa? mistä kuljetettiin gladiaattorit ja mistä villieläimet? miten monituhatpäinen yleisö johdatettiin paikoilleen, ja mitä he ajattelivat näistä verisistä näytöksistä?. Miten areena puhdistettiin taistelujen jälkeen? missä keisarin aitio sijaitsi? jne. Colosseum on jotakin sellaista, mitä ei pysty ymmärtämään katselemalla dokumentteja televisiosta tai lukemalla kirjoja. Se pitää itse nähdä ja kokea ennen kuin pystyy täysin ymmärtämään sen mahtavuuden.Colosseum on raunioituneenakin erittäin vaikuttava rakennus.

Kun Colosseumin historiaa aletaan pohtimaan syvällisemmin, on lopputulos se, että Colosseumin maine on veren tahrima. Mutta se ei kuitenkaan riitä, että me tuomitsemme amfiteatterin. Me emme pysty myöskään ymmärtämään kansaa, joka halusi muuttaa ihmisuhrit koko kaupungin yhteiseksi huvitukseksi. Näissä tappajaisissa gladiaattorit olivat aseistettuja vain, jotta he voisivat tappaa toisiaan viihdyttääkseen roomalaisia. Kirjailija Plinius nuorempi on todennut vuoden 100 tienoilla, että gladiaattoritaistelut innoittivat miehiä altistamaan itsensä kunniakkaille haavoille ja halveksimaan kuolemaa, kun he näkivät gladiaattorin palavan voitonhalun.Ensimmäisellä vuosisadalla eKr. kansa oli päässyt näiden teurastusnäytäntöjen makuun siinä määrin, että virkoihin pyrkijät kalastelivat ääniä järjestämällä niitä kansalle. Colosseumin veriset näytökset vetivät massoittain yleisöä. Ne olivat “keisarin lahjoja kansalle”.Näytökset herättivät katsojissa tunteita, joiden moraalista laatua jälkipolvien on vaikeaa arvioida, koska aika ja kulttuuri johon kyseiset esitykset liittyvät poikkeavat niin paljon nykyisestä.

Gladiaattorit olivat usein sotavankeja ja rikollisia. Roomalaisten suhtautumistapa heihin oli kaksijakoinen. Toisaalta heitä halveksittiin, toisaalta ihailtiin. Käytännössä taistelijat olivat yhteiskunnan alinta kastia. Yleensä gladiaattorit olivat sotavankeja, rikollisia ja orjia, jotka gladiaattorikoulu oli ostanut, mutta heidän joukossaan oli myös vapaita kansalaisia, jotka olivat vapaaehtoisesti valinneet taistelijan ammatin. Tähän valintaan ovat saattaneet vaikuttaa esim. velkaantuminen tai yksinkertaisesti taistelunhalu.

Rooman valtakunnan historia on sotaisa. Keisari toisensa jälkeen laajensi määrätietoisesti imperiumiaan, mikä aiheutti levottomuuksia erityisesti rajaseudulla. Kun Colosseum otettiin käyttöön vuonna 80, Rooma oli jo vakiinnuttanut asemansa johtavana valtakuntana. Imperiumin ytimessä vallitsi rauha, jota tavallinen kansa oli ehkä alkanut pitää itsestään selvänä asiana. Gladiaattorit muistuttivat omalla tavallaan rahvasta siitä, että taistelutahtoa tarvittiin yhä, vaikka armeija koostuikin ammattisotilaista, jotka uhrasivat tarvittaessa henkensä yhteisen hyvän vuoksi.

Colosseumin rakennusmuoto

Nykyisessäkin kunnossaan Colosseum pystyy antamaan kuvan siitä, millainen oli roomalaisen amfiteatterin tyypillinen rakennusmuoto täydellisemmillään toteutettuna.

Colosseum on rakennettu kovista ja kiinteistä travertiinijärkäleistä, jotka olivat peräisin Tiburin, nykyisen Tivolin, lähellä sijainneesta Albulean louhoksesta. Ne kuljetettiin Roomaan tätä tarkoitusta varten raivattua kuuden metrin levyistä tietä pitkin. Colosseum on 188 metrin pituinen ja 156 metrin levyinen soikio, jonka ympärysmitta on 527 metriä. Sen nelikerroksinen seinämuuri on 57 metriä korkea. Kolmen ensimmäisen kerroksen mallit on luultavasti saatu Marcelluksen teatterista. Ne koostuvat kolmesta päällekäisestä holvikaarisarjasta, joissa oli alunperin koristeina kuvapatsaita ja joiden ainoana erona ovat niissä käytetyt pylväsjärjestelmät. Alhaalta päin lukien doorilainen, joonialainen ja korinttilainen. Neljännessä kerroksessa on umpimuuri. Pilasterit jakavat sen kenttiin, joissa antiikin aikana vuorottelivat ikkuna-aukot ja pronssikilvet. Jokaisen ikkunan yläpuolella on kolme konsolia, joiden kunkin kohdalla on kattolistassa reikä. Konsolit kannattelivat tankoja, joiden varaan joukko laivaston merisotilaita kiinnitti hellepäivinä suuren purjekankaan suojaamaan areenalla taistelevia gladiaattoreita ja katsomossa istuvaa yleisöä. Katsomo alkoi neljä metriä ylempää kuin areena. Siinä oli ensimmäisenä pronssiaitauksen suojaama tasanne, jossa ylimystön edustajat istuivat marmoriistuimillaan. Tasanteen takana kohosivat muun yleisön istumaportaat, jotka jakaantuivat kolmeen vyöhykkeeseen. Ensimmäisen ja toisen vyöhykkeen erotti kolmannesta matalien seinien reunustamat käytävätasanteet. Kustakin vyöhykkeestä johti alas joukko käytäviä, jotka purkivat katsojajoukot sisään ja ulos. Ensimmäisessä vyöhykkeessä oli kaksikymmentä porrasta, toisessa kuusitoista. Toisen ja kolmannen vyöhykkeen välissä oli viiden metrin korkuinen ikkunallinen ja ovellinen muuri. Kolmannessa vyöhykkeessä istuivat naiset ja sen takana olevalla, ulkomuuriin ulottuvalla terassilla seisoivat vierasmaalaiset ja orjat, joilla ei ollut oikeutta osallistua pääsymerkkien jakoon.