New Open Access Article- New Developments in Lithic Analysis: Laser Scanning

and Digital Modeling

http://www.saa.org/AbouttheSociety/Publications/TheSAAArchaeologicalRecord/tabid/64/Default.aspx

New Open Access Article- New Developments in Lithic Analysis: Laser Scanning

and Digital Modeling

http://www.saa.org/AbouttheSociety/Publications/TheSAAArchaeologicalRecord/tabid/64/Default.aspx

Reading this article about a robbery early this morning at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam has got me thinking: how does a museum carry on after being the victim of such a terrible crime? You need to decide not only how to handle the crime, but also how to communicate about it.

Communication is key

As a curator or director, you’re removed from direct contact with the public – through a veil of press releases and official statements, you can pick and choose which aspects of your recovery are distributed by the media.

But as a docent, you’re thrust into the spotlight of the scandal. Facing wave after wave of museum-goers, only made more thirsty by the standard day of closure following the theft, how do you deal with the questions? Chances are, you don’t even know the answers. And even if you do, it’s doubtful that the administration wants you letting everyone and their brother know that someone left the employee entrance unlocked and twelve hours later you were a few Picassos lighter.

Great balls of fire

Disasters hit museums in any number of ways, whether they be manmade or natural. During my time as a volunteer at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. (a fantastic private collection if you’re looking for something off the Smithsonian-beaten-track and don’t mind paying for it), there was a minor fire in one of the buildings. It happened during renovation work, and the Phillips handled the situation masterfully: the staff were quick to rescue works, the next special exhibition was installed on time, and they waived the admission fee for the rest of the month. Granted, half of the museum was closed to visitors, but you could still see, among other works, Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party, the feather in the Phillips’ cap.

The fire went as well as a fire could go in an art gallery, but reporting to volunteer the day after the disaster, I found myself a little out of my depths. Having gotten a quick debriefing from the volunteer coordinator on the details of the fire, I was told not to say too much and just reinforce the fact that a) nothing was damaged and b) admission was free. Sitting at my little wooden table where I was accustomed to pointing people to the loo and giving out restaurant recommendations, I faced one breathless patron after another. Unable to answer any of their salacious questions (which I would have liked to know the answers to, as well), I could see the disappointment on their faces.

What now?

For the Kunsthal, today marks a pivot point full of potential. They can approach the situation in any number of ways, but I hope they do so with finesse and honesty. Preparing their employees and volunteers for the onslaught of difficult questions is the first step. The second, and far more important, step is being completely open about the recovery process. Priceless works of art are stolen every day, and by denying that the damage is as extensive as it is, or covering up damages, museums are denying the significance of their victimization.

The largest property theft in U.S. history is the Isabella Stewart Gardner theft of 1990, and yet it is still unsolved. Museums in the Mediterranean are being assailed with minor thefts as the economic crisis worsens, work taken by Nazis continues to be fought over, and galleries continue to display illegally obtained artifacts.

In the 21st century, I would hope that the Kunsthal takes this opportunity to not only rally public support for the return of these particular artworks, but also to start a conversation about the state of stolen art around the world today. By telling their employees to guide visitors away from tricky questions about the crime, the museum administration would essentially be telling their employees to maintain the view that stolen art is not a big deal.

Art elucidates, challenges, denies, rejects, speaks, cries, and completes us. When a work of art is stolen, it affects all of us, not just the museum or its employees. It’s time for stolen art to move from the culture section to the front page.

Apologies for this post being quite rambly, it’s basically all of my reactions to the article in a big ol’ chunk of text. Writing this has really struck a chord in me – definitely look out for more thoughts on how museums respond to thefts like this one, as well as the perception of stolen art in the law, politics, and media.

The Penn Museum has started a new touch tour program, where visually impaired visitors can interact with exhibits in new ways (Source: The Daily Pennsylvania).

“Doug Trinidad runs his hands over a 3,200-year-old sphinx.

“This is so sick,” he exclaims, as his fingers feel the engraved hieroglyphics around the base.

Since I last blogged about the topic of Christopher Rollston’s situation at Emmanuel Christian Seminary, a lot has appeared not only on blogs, but in Inside Higher Ed, which carried a story about what has been going on. That article suggested that the Emmanuel Christian Seminary administration was choosing to pander to a potential donor (and pursue a large donation) rather than respect the wisdom and insight of a valuable professor. Bob Cargill offers further comments on that topic, as does Jeremiah Bailey.

Since I last blogged about the topic of Christopher Rollston’s situation at Emmanuel Christian Seminary, a lot has appeared not only on blogs, but in Inside Higher Ed, which carried a story about what has been going on. That article suggested that the Emmanuel Christian Seminary administration was choosing to pander to a potential donor (and pursue a large donation) rather than respect the wisdom and insight of a valuable professor. Bob Cargill offers further comments on that topic, as does Jeremiah Bailey.

Matthew Worsfold wrote an open letter from a student in support of Rollston.

Steve Caruso emphasizes that, while religious institutions have the right to demand that employees hold certain views, Rollston’s case does not involve a departure on his part from his seminary’s statement of faith.

Of related interest:

Fred Clark asks who’s afraid of Rachel Held Evans.

Pete Enns discusses inerrancy.

Richard Beck asks whether patriarchalists can pray the Lord’s Prayer.

Libby Anne looks at Christians who actually adopt more of the values the Bible reflects, about which Rollston spoke, and which his opponents at ECS would presumably not embrace.

See also the posts I added belatedly to my previous round-up, by Chris Heard and Chris Keith, and also the discussion under that earlier post.

I always protest a little too much when I say that I’m not really all that interested in historical archaeology. It is true, the Anatolian/Aegean Neolithic still holds me firmly in thrall. It’s more that historical archaeology draws me in a little too much, I get a little too obsessive about the documentary history and the amount of crazy detail you can find about who owned the land when, what kind of forks they used, who manufactured the forks, and oh did you know that the forks were sold by a tinker in Kent at the same time? My enthusiasm for ephemera and marginalia kicks in and it all gets to be a little bit too much.

Needless to say, 100 Minories has a long historical background and I got a chance to skim the surface during my last week on the project, looking through fantastic sites like Spitalfields Life for information about the area surrounding the site. On a chance search for information about the Navigation School that was once held in the Brutalist 1960s on the site I found information about a much earlier school of navigation that was once held on the site.

Come closer, my friend.

An engraving of the 1707 disaster.

In 1707, one of the worst maritime disasters claimed famed Rear Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, who lost several ships at sea in the Isles of Scilly with over 1,400 men on board. They were lost in stormy weather, unable to calculate their position. The British parliament’s reaction to this horrible loss of life was to create a Board of Longitude in the Longitude Act of 1714. They created a prize ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 pounds to discover a ‘practicable and useful’ way to determine longitude at sea.*

Born in Wolsingham, County Durham on May 13th, 1804, Janet’s brilliance was perceived early and she received a national scholarship to attend Queen Charlotte’s school in Ampthill, Bedfordshire. She married a George Taylor Jane, had eight children and lived her life near the Thames docks. By then she was an established author of nautical treatises and textbooks, and established her own Nautical Academy not far from the Tower of London. 104 Minories, in fact.

In 1834 Janet Taylor invented the Mariner’s Calculator, a device that enabled the finding ‘the true Time’,'the true Altitude’, ‘the true Azimuth’, ‘Latitude by double Latitudes and elapsed Time’, among many other applications. Sadly, after testing at sea, the instrument was determined to be too delicate for the ‘clumsy fingers of seamen’ noted to be like ‘sausages’ so it was not widely adopted. Still she received gold medals of recognition for her contributions to the maritime community by the king of Prussia, the king of Holland and even by the Pope. After the death of her husband she put into dire financial straits, and was given a Civil List pension of £50 per year.

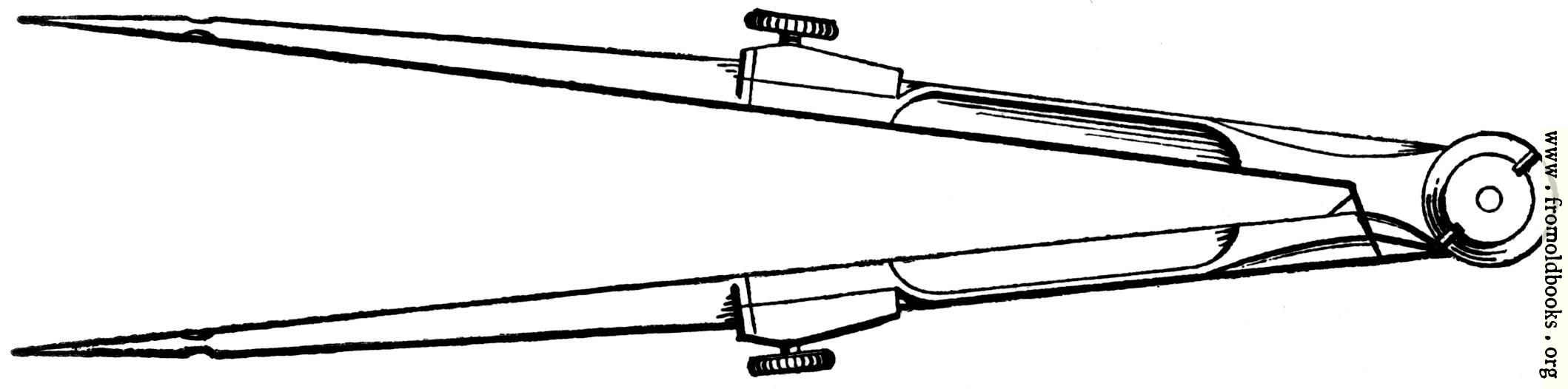

When I mentioned all of this to Guy Hunt, he was excited. It is very possible that the First Lady of Navigation had conducted her Nautical Academy on the site and it is equally possible that when we go to full excavation that we’ll find building foundations and rubbish dumps that could possibly be associated with the trade at the time. The thought is made even more tempting by a single artifact, unremarkable at the time–we found a pair of compass dividers on site.

So, on a day dedicated to women in technology, this post is devoted to the only woman in the 2,200 entries in The Mathematical Practitioners of Hanoverian England 1714-1840, Mrs. Janet Taylor. Happy Ada Lovelace day!

*This post heavily references John S. Croucher and Rosalind F. Croucher’s Mrs Janet Taylor’s ‘Mariner’s Caluclator’: assessment and reassessment in The British Journal for the History of Science, 44:4, 493-507. I understand that there is a longer book coming out by the Crouchers regarding Mrs. Janet Taylor, which I look forward to reading!

By:  Micaela Carignano, 2012 Heritage Fellow

Micaela Carignano, 2012 Heritage Fellow

This summer, thanks to an ASOR Heritage Fellowship, I traveled to Cyprus to participate in the Kalavasos and Maroni Built Environments Project (KAMBE). The project, led by Sturt Manning of Cornell University and Kevin Fisher from the University of Arkansas, focuses on several Late Bronze Age sites in southern Cyprus. Most of the research has involved the use of geophysical techniques to survey the landscapes surrounding previously excavated LBA sites.

This season, I joined a group of students who worked alongside the geophysics team excavating some of the features that showed up in the survey data. We started our work at the site of Maroni-Tsaroukkas, which was excavated by the British Museum in 1897, and later in the 1990s by a team led by Dr. Manning. After some days of intense weeding to remove the thorny scrub that had grown since the last excavations, we opened small trenches immediately adjacent to those dug previously. This was difficult because the excavators on the British Museum expedition had dotted the terrain with large pits in their search for intact ceramic vessels. We were able to work around the pits to some extent, however. In one trench where I worked, instead of finding the continuation of a Building 1 wall, as we expected, we dug through a thick red clay deposit that contained some of the earliest ceramics on the site—an exciting find! Later we dug a test trench in a nearby hayfield, where we confirmed a feature found in the geophysics surveys. Throughout the season we took turns helping to re-bag and re-tag dozens of crates full of finds from previous excavations and surveys that had been stored in a rat-infested shed for years. This task culminated in an exciting trip to deliver the artifacts to the Larnaca Archaeological Museum, where they will fare much better in the future.

I greatly enjoyed my experience on the KAMBE excavation and my first trip to Cyprus. It proved to be a beautiful island which I hope to revisit as I continue my graduate studies. I am extremely grateful to the generous donors to the Heritage Fellowship and to ASOR for helping me travel to Cyprus and participate in this project.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

New Open Access Article-Nasal floor variation among eastern Eurasian Pleistocene Homo

From Whence and Wherefore Were the Trees? Some Critical Thoughts on the Ustrinum Domus Augustae

By Christopher Villeseche

Published Online (2012)

“Earth and heaven intersect at the pyre…” - Paul Rehak

Historical evidence suggests that Augustus Caesar, first Emperor of Rome, was a person who liked to plan ahead. His predilection for preparedness is perhaps most apparent when we consider the details pertaining to the end of his life. When he was a young man, even before he took on the responsibility or title of Augustus, the fledgling Emperor commissioned the construction of his own tomb and later on prepared “detailed instructions regarding his funeral.” Indeed, it would seem that the most powerful ruler in the Classical world spent much of his life pondering over the occurrence and implications of his own demise.

The first Imperial funeral was apparently a solemn, precedent-setting affair. The historians Suetonius and Cassius Dio describe funerary proceedings that began in the Forum and ended in the Mausoleum, both sites abundantly attested in the architectural topography of Rome. Yet it was at a venue somewhere between these locations that the procession stopped for the most dramatic and perhaps most meaningful part of the ceremony – the cremation of the deceased Emperor’s body.

Having been conveyed through the city “on the shoulders of senators,” the body was placed on a pyre inside of a unique crematory structure called an ustrinum in Latin. Various rites were performed around it and tokens of honour were heaped upon it and then the whole thing was set ablaze. At the peak of the ceremony an eagle was released, “appearing to bear his spirit to heaven.” The Emperor’s wife and distinguished associates remained inside the ustrinum for several days before carrying on with the concluding phase of the funeral.

While the histories present a fairly detailed account of events that took place in and around the ustrinum, there is preserved in the literary record only one passage that describes the structure itself. Just a few years after the death of Augustus, the travelling scholar Strabo published his work Geographica, in which are recorded observations of many places throughout the ancient world. In his notes on the Campus Martius the geographer gives particular consideration to the “most remarkable” Mausoleum of Augustus, and then turns his attention to a site located some unknown distance away, in some undetermined direction:

“… in the centre of the Campus is the wall (this too of white marble) round his crematorium; the wall is surrounded by a circular iron fence and the space within the wall is planted with black poplars.”

It seems that apart from this vague reference, every other memory or mention or material trace of the ustrinum simply faded into obscurity over millennia. However, ruins and artefacts uncovered in recent centuries have prompted scholars to consider more closely the possible location and layout of the nearly-forgotten structure. For the humble purposes of this casual assessment it will be necessary to consider scholarly interpretations of archaeological evidence but for the moment we will rely on the ancient sources and on our own plain reasoning to formulate an opinion. Before anything else, we must attempt to get oriented.

The ruins of the Mausoleum are located just a few hundred feet from the Tiber River at the north end of the Campus Martius. Where, then, in relation to this point, might be the location that Strabo considered “the centre of the Campus”? With due consideration given to the “marvellous” size and the rough boundaries of the area, we can reasonably surmise that the geographer was referring to a site somewhere to the south or southwest, near to the natural centre of the river-bounded plain. However, this is just a passing observation, an assertion of nothing more than likelihood; we are yet far from reaching any conclusions.

Regardless of the precise location of the ustrinum, close consideration allows us to deduce that in terms of physical dimensions it was quite large. Common sense and Cassius Dio both suggest that a pyre of considerable size was required to achieve successful cremation and/or sufficient dramatic effect. Beyond this was required room to accommodate the processional march round the pyre undertaken by priests and soldiers. How much further out, then, might have stood the trees and marble boundary? The interjection might be made that no fixed perimeter was erected around the pyre until sometime after the cremation ceremonies were completed. After all, it does seem somewhat counter-intuitive to suppose that the intended site of a large conflagration would have been enclosed with flammable foliage and delicate marble facing. However, if we reflect upon the simple mechanics involved in maintaining a good fire on a windy plain we realize that the surrounding barrier of solid stone and tall trees was likely an elementary expedient intended to facilitate and contain the long-burning blaze of a funeral pyre. Thus we may begin to imagine an ustrinum that appears more like a precinct or small park than a confined utilitarian structure.

Regardless of the precise location of the ustrinum, close consideration allows us to deduce that in terms of physical dimensions it was quite large. Common sense and Cassius Dio both suggest that a pyre of considerable size was required to achieve successful cremation and/or sufficient dramatic effect. Beyond this was required room to accommodate the processional march round the pyre undertaken by priests and soldiers. How much further out, then, might have stood the trees and marble boundary? The interjection might be made that no fixed perimeter was erected around the pyre until sometime after the cremation ceremonies were completed. After all, it does seem somewhat counter-intuitive to suppose that the intended site of a large conflagration would have been enclosed with flammable foliage and delicate marble facing. However, if we reflect upon the simple mechanics involved in maintaining a good fire on a windy plain we realize that the surrounding barrier of solid stone and tall trees was likely an elementary expedient intended to facilitate and contain the long-burning blaze of a funeral pyre. Thus we may begin to imagine an ustrinum that appears more like a precinct or small park than a confined utilitarian structure.

So much we have gathered from our own reading of the ancient literary sources. Before moving on to consider the contributions of modern researchers and scholars, we will pause briefly to emphasize particular points about the black poplar trees. If, as we have suggested, the trees constituted a functional aspect of the ustrinum then it goes without saying that they were planted by order of Augustus himself at some time well before his death and cremation (the question of why he might have chosen black poplars is one that we have explored elsewhere). With these things established in our minds as reasonable and most likely true, we proceed to consider the matter in the light of scholarly purview.

Today, material evidence is the fulcrum for any discussion of Augustus’ crematorium. During the late 18th century, excavations undertaken just a few hundred feet to the east of the Mausoleum by one R. Venuti uncovered stone remains that were at once intriguing and suggestive. The ruins consisted of a small travertine-paved area on which were scattered a number of cippi inscribed with the names of Imperial family members; of six cippi, three bore an epitaph that read “here was burnt” while three others bore an epitaph that read “here was lain.” No evidence of wall footings was found.

On the basis of these finds, scholarly opinion about the long-missing ustrinum is divided. Among those who believe that the ruins represent the actual site of the first Emperor’s cremation is Dr. M. Boatwright; in her treatment of “problematic Roman ustrina,” she references the Venuti ruins as a model of practical crematory design. Among those who believe that the cremation site should be sought after elsewhere is the late Dr. P. Rehak; in his interesting work on the esoteric aspects of Augustan architecture, he notes that the Venuti ruins are “attractive” yet altogether inconsistent with the antecedent documentary evidence. Apparently neutral in the matter is Dr. D. Noy, whose informative article on ruined Roman cremations is highly germane to the matter under our consideration. Among other things he tells us that a disorganized or mismanaged cremation was a sure sign of poverty or shame; that the construction and maintenance of a funeral pyre was surely “a skilled task”; that it was important to safeguard against natural forces, such as wind. Altogether, what can we learn from these learned opinions?

In the end we can more confidently hold to our original understanding of the sources. We have found much to support and very little to refute our ideas about the location of the ustrinum, and we have posited an important point about the role of the tell-tale trees in the overall layout of the site. Indeed, in all that we’ve covered it seems clear that a proper cremation – one befitting a grand Imperial funeral – would have called for considerable preparation. And of course we know that Augustus Caesar, first Emperor of Rome, was a person who liked to plan ahead.

Works Cited

Boatwright, Mary T. “The ‘Ara Ditis-Ustrinum of Hadrian’ in the Western Campus Martius and other Problematic Roman Ustrina.” American Journal of Archaeology 83.3 (1985): 485-497. JSTOR. Web.

Noy, David. “‘Half-Burnt on an Emergency Pyre’: Roman Cremations Which Went Wrong.” Greece & Rome, Second Series 47.2 (2000): 186-196. JSTOR. Web.

Platner, Samuel B., Thomas Ashby. “A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome.” Perseus Digital Library. From 1987, ongoing. Web.

Rehak, Paul. Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006. Print.

Strabo, trans. Hamilton, H.C. “Geography.” Perseus Digital Library. From 1987, ongoing. Web.

See also: Augustus Caesar and the Exile of Ovid: a Mystery Revisited

This is a title that references the bellicose storm god , and “warlord”, I think, is an appropriate, if rough, gloss. (I think the title would have fit somewhere between our own titles warlord and emperor ...). That said, I don’t think this is a title that should be translated as “warrior” as I see little reason to believe that the person holding the title actually was directly axing people and/or places.Whether K'abel ever strode into battle and axed a living enemy is unknown. The title is certainly military but it might mean no more (and no less) than Queen Elizabeth II's rank of "Commander-in-Chief of the British Armed Forces". It's likely, though, that as Kaloomte, she served as military governor of the el-Peru kingdom under the auspices of the House of the Snake King, to which she belonged.

She had a long life, and she was a powerful woman who was depicted as such. That's important, because history remembers her as a formidable figure with a supreme title.Formidable. Yes indeed. Figuratively ... and now literally. She was a big woman.

Dynastic marriage patterns, in which powerful families sealed alliances by marrying off young women to less powerful ruling families at other sites, virtually demand that we expect many sites to yield evidence of noble or ruling women whose status might be higher than that of their local spouse.And indeed they do. An elite circle, to be sure, but a well-peopled one. By now, we should get used to it: "The fact that there were women powerful enough to be buried with the greatest degree of celebration possible in the Classic Maya world should no longer come as a surprise."